Indonesia’s oil palm industry is moving east. With large tracts of land increasingly difficult to find in Sumatra and Borneo, plantation companies are now focussing their attention on Indonesia’s eastern frontier: the small islands of the Maluku archipelago and especially the conflict-ridden land of West Papua.

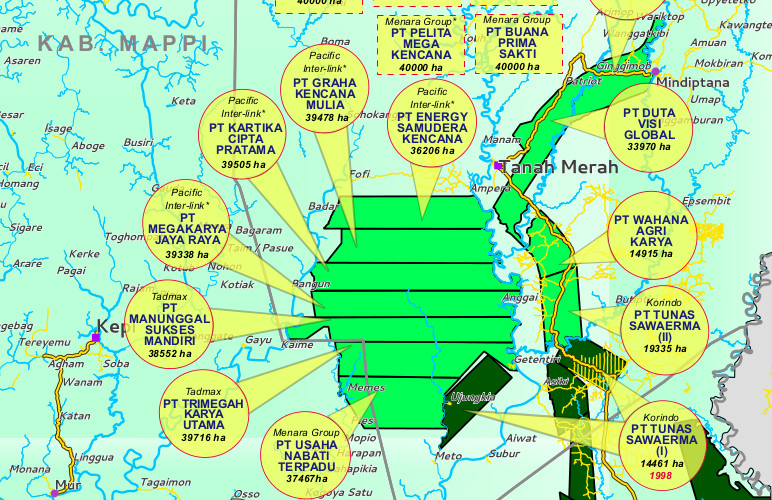

In 2005 there were only five oil palm plantations operating in West Papua ((the two provinces of Papua and West Papua)). By the end of 2014 there were 21 operational plantations. This rapid expansion is set to continue with another 20 concessions at an advanced stage of the permit process, and many more companies that have been issued with an initial location permit. If all these plantations were developed, more than 2.6 million hectares of land would be used up, the vast majority of which is currently tropical forest.

Almost without exception, these plantations have caused conflict with the local indigenous communities who depend on the forest – lowland Papuans are mostly hunters and gatherers to some degree. The conflicts have centred around community’s refusal to hand over their land, demand for justice in the cases where they feel the land has been taken from them by deceit or intimidation, horizontal conflicts between neighbouring villages or clans, action by indigenous workers who feel they are exploited, or aggression by police or military working as security guards for the plantation companies.

The West Papua Oil Palm Atlas, published by awasMIFEE, Pusaka and six other organisations, is an attempt to provide a picture of this developing industry. Who are the companies involved? Where are they operating? Which areas will be the next hotspots? The aim is to be part of a process to push for more open and accessible information about resource exploitation industries in West Papua – currently local administrations and companies are often reluctant to share information about permits, meaning that communities often know nothing of plantation plans until a company shows up, trying to acquire their land.

Indonesian law does recognise communal land rights for indigenous customary communities, but in reality those communities often face considerable pressure to give up that land, and are rarely given more than US$30 per hectare in compensation. It is hoped that this publication can become a tool for indigenous peoples and social movements who wish to understand the oil palm industry and defend their forest against these land grabbers, as they themselves should be the ones to determine what kinds of development will benefit their communities.

For environmentalists and supporters of indigenous struggles around the world, we hope that this will also be a useful insight into the dynamics of the plantation industry and the threats it is causing in the third largest tropical forest in the world. Using the excuse of the conflict around the independence movement, the Indonesian government makes it very difficult for international observers to access West Papua, and this has probably also resulted in a lack of awareness internationally about the ecological threats. Yesterday (29th April) human rights groups throughout West Papua, Indonesia and in over 22 cities around the world held demonstrations for open access to Papua, which has long been a demand of many Papuan movements. Publishing this Oil Palm Atlas is also an attempt to break the isolation of Papua, by focussing attention on the issue of indigenous land rights, in a context where local communities which choose to oppose plantation companies often feel intimidated by state security forces which back up the companies.

Download the atlas here: [English] [Indonesian]

3 Trackbacks

[…] Available for download: https://awasmifee.potager.org/?p=1205 […]

[…] Kalimantan è oggi, e Papua è domani. Questo domani potrebbe anche essere già arrivato. Un nuovo rapporto mette in luce la rapida espansione delle piantagioni di palma da olio nell’area della Nuova […]

[…] Kalimantan è oggi, e Papua è domani. Questo domani potrebbe anche essere già arrivato. Un nuovo rapporto mette in luce la rapida espansione delle piantagioni di palma da olio nell’area della Nuova […]