In September 2014, in his last month in the role before handing over to the new administration, former forestry minister Zulkifli Hasan carelessly condemned hundreds of thousands of hectares of Papuan forest to development by logging and plantation industries.

Joko Widodo had won the Indonesian presidential rlection on 9th July 2014, and Zulkifli Hasan’s National Mandate Party (PAN) was not to be part of the new ruling coalition. With the knowledge that he would not be in his post much longer, the rate of new ministerial decrees (Surat Keputusan) started to grow exponentially, until his last week in office, when over 100 decrees were signed. Many of these established new concessions for logging and timber companies, or released land from the forest estate for oil palm plantation companies.

Decrees were issued on forest land throughout Indonesia, but Papua was especially severely affected. From late August to the end of September, ten oil palm plantations were given forest release permits (212,216 hectares), six more were given in-principle permits (173,389 ha), two industrial timber plantations got permits (178,980 ha), as did one logging concession (234,470 ha). That’s a total of 799,055 hectares – an area considerably larger than the island of Bali, earmarked for destruction in just over a month. Almost half of these permits were signed on a single day: Zulkifli Hasan’s very last day in the job, 29th September 2014. (( He left his post on 1st October, a few weeks before the official transition to the new cabinet, because he was selected to take up a position as the head of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR), the post he currently still holds.)) In the rush to sign permits, as will be seen below, basic environmental protection was ignored.

|

|

Company |

Regency |

Permit |

Reference |

Area |

| 13/08/2014 | PT Permata Nusa Mandiri |

Jayapura | Release of land from forest estate |

SK.680/Menhut-II/2014 | 16182 |

| 29/08/2014 | PT Surya Lestari Nusantara |

Mappi | In-principle forest release |

SK S.382/Menhut-II/2014 |

36145 |

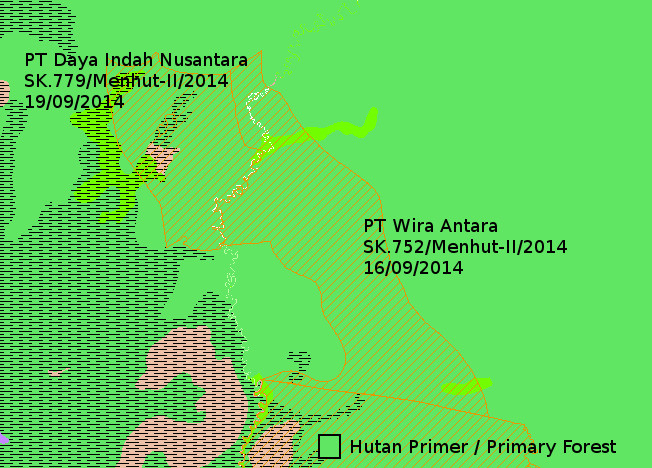

| 16/09/2014 | PT Wira Antara |

Jayapura | Release of land from forest estate |

SK.752/MENHUT-II/2014 | 20264 |

| 19/09/2014 | PT Daya Indah Nusantara |

Sarmi | Release of land from forest estate |

SK 779/MENHUT-II/2014 |

10576 |

| 24/09/2014 | PT Bangun Mappi Mandiri |

Mappi | In-principle forest release |

SK S.429/Menhut-II/2014 |

18006 |

| 25/09/2014

|

PT Global Papua Abadi |

Merauke | In-principle forest release |

SK S.435/Menhut-II/2014 |

20370 |

| PT Anugerah Rejeki Nusantara |

Merauke | In-principle forest release |

SK S.437/Menhut-II/2014 |

39730 | |

| PT Kesatuan Mas Abadi |

Teluk Bintuni |

Industrial Forestry Concession |

SK.818/Menhut-II/2014 | 99980 | |

| 26/09/2014

|

PT Prima Sarana Graha |

Mimika | In-principle forest release |

SK S.448/Menhut-II/2014 |

21240 |

| PT Duta Visi Global |

Boven Digoel |

Release of land from forest estate |

SK.830/Menhut-II/2014 | 33975 | |

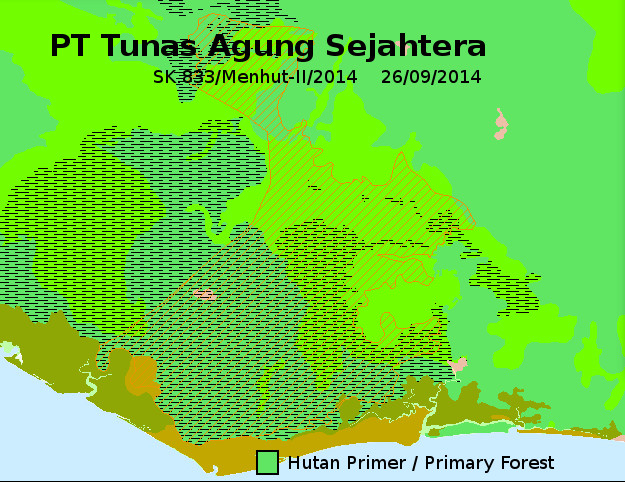

| PT Tunas Agung Sejahtera |

Mimika | Release of land from forest estate |

SK.833/Menhut-II/2014 | 39500 | |

| 29/09/2014 | PT Berkat Cipta Abadi |

Boven Digoel |

Release of land from forest estate |

SK.835/Menhut-II/2014 | 14435 |

| PT Visi Hijau Nusantara |

Boven Digoel |

Release of land from forest estate |

SK.838/MENHUT-II/2014 | 24187 | |

| PT Tunas Sawaerma |

Boven Digoel |

Release of land from forest estate |

SK.844/Menhut-II/2014 | 19001 | |

| PT Wahana Agri Karya |

Boven Digoel |

Release of land from forest estate |

SK.855/Menhut-II/2014 | 14728 | |

| PT Hanurata |

Fakfak | Logging Concession |

SK.859/Menhut-II/2014 | 234470 | |

| PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa |

Tambrauw | Release of land from forest estate |

SK.873/Menhut-II/2014 | 19368 | |

| PT Wahana Samudra Sentosa |

Merauke | Industrial Forestry Concession |

SK.880/Menhut-II/2014 | 79000 | |

| PT Menara Wasior |

Teluk Wondama |

In-principle forest release |

SK S.466/Menhut-II/2014 |

28880 |

Table: List of companies issued permits in Papua in late August and September 2014.

In addition to these permits, on 27th August, Hasan signed a decree accepting many proposed changes to the forest estate to accommodate the spatial plan of Papua Barat province. This decree, SK. 710/Menhut-II/2014, removed 243,045 hectares of land from the forest estate, meaning future development is much more convenient. This was followed up on 22nd September by decree SK.783/Menhut-II/2014 which defined a new map of the forest estate. (( Unlike regulations, ministerial decrees are not often put online by the government itself, this one can be read at this scribd link: https://www.scribd.com/presentation/354546863/Kawasan-Hutan-Provinsi-Papua-Barat )) The two maps were not even the same, because consent is needed from the House of Representatives to remove land from the areas designated as strategic conservation zones. This is an indication of a rushed decision.

This last-minute rush to issue more and more decrees which would benefit companies raises questions of corruption: was Zulkifli Hasan trying to cash in from companies hoping to get their permits approved before the change in government, or was he simply trying to clear his desk before moving on? There is some evidence for the latter explanation, since as well as the permits, 16 ministerial regulations were also issued during the last week in September, many of which serve no particular vested interests.

Whether corruption was involved or not, incompetence certainly was. Many of the decisions to grant permits were taken without due attention to detail and violated the ministry’s own regulations. Three years later, some of the plantations granted permits at that time are close to starting clearing forest (one has already started, PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa, which local people are currently resisting), Zulkifli Hasan’s office clearance permit bonanza is starting to have a real effect on the lives of indigenous Papuans. The biggest threat, currently, comes from oil palm plantations.

Forest land released for plantations.

According to the ministry regulations valid in 2014 (Permenhut 28/2014 article 7, signed on 13th May 2014), a company can only apply for permission to release land from the forest estate if it already holds a plantation business licence (IUP), for which it must have had an environmental impact assessment approved. Not one of the ten companies for which forest estate land was released had obtained this licence at that time, meaning the forest land should never have been released. Several of the companies have, however, obtained it since. (( PT Tunas Agung Sejahtera was given an environmental permit in December 2014, and the IUP followed in 2015. PT Tunas Sawaerma and PT Berkat Cipta Abadi were issued environmental permits in June 2015, PT Wira Antara and PT Daya Indah Nusantara were given IUPs in 2016. The permit situation in PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa is still a little unclear, but it was known that a hearing for an environmental impact assessment was held in September 2016. PT Visi Hijau Nusantara, PT Wahana Agri Karya and PT Duta Visi Global’s EIAs were rejected in 2013 because of local opposition, but PT Wahana Agri Karya applied for an EIA again in 2017. No information is available to suggest that PT Permata Nusa Mandiri ever obtained either a EIA or IUP. ))

For some of the concessions Hasan’s failure to ensure permits comply with regulations is even more clear. In the case of PT Tunas Sawaerma, a part of the land was peatland, which was at the time (and still is) included in the maps of Indonesia’s moratorium on new permits in primary forest and peatland. Normally the Forestry Ministry will not release land in these circumstances, as it is a clear violation of its own moratorium.

For PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa, the decree from the minister stated 19368 hectares would be released, less than the amount the company had applied for, because there was 13021 hectares of primary forest within the concession which would not be released. (( The forest release document states: “Terhadap areal hutan primer seluas 13.021,73 hektar yang berada di Hutan Produksi yang dapat Dikonversi yang akan dilepaskan untuk perkebunan kelapa sawit atas nama PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa dikeluarkan dari pelepasan kawasan hutan dan ditindaklanjuti dengan tata batas” )) But somebody at the ministry evidently forgot to coordinate with the cartographers, because the maps of area released show an area of over 32000 hectares, including all this primary forest.

Three years later.

Three years have passed since September 2014. Most of these plantation plans have still not yet been realised, and the forest is still there – for now. However, none of the plans are known to be abandoned:

- PT Berkat Cipta Abadi and PT Tunas Sawaerma are part of the Korindo group, which owns several plantations in the Merauke and Boven Digoel area, including other working concessions operated by PT BCA and PT TSE. Korindo has currently imposed a moratorium on new forest clearing, as a result of campaigns which have challenged palm oil buyers with no-deforestation policies. However its long-term commitment to halting deforestation is doubtful, as it is also engaged in aggressive campaigning and lobbying locally, claiming it needs to expand to meet promises to local smallholder co-operatives it has formed. The fate of its undeveloped concessions is therefore dependent on how it eventually responds to the changing demands of the industry.

- PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa was bought by a company believed to be part of the Salim Group just before the minister’s decision in 2014. After the forest land was released for an oil palm plantation, the company faced local opposition, but it started applying for new permits to growing corn instead, and from a small test area, expanded in 2017 to clearing and planting thousands of hectares in the Kebar valley, an area of grassland surrounded by forests in Tambrauw Regency, Papua Barat. It is still not clear exactly what locally-issued permits the company has obtained to justify the change from oil palm to corn, although local activists are trying to investigate. There is substantial community opposition in the Kebar valley.

- PT Tunas Agung Sejahtera’s concession is a remote area in Mimika Regency on the south coast of Papua. The former owners were members of the Yasa family, brokers who have successfully sought permits for plantations throughout Papua. They are believed to never have operated any plantations themselves but sell them on to other companies, including Austindo Nusantara Jaya and the Noble Group. PT TAS struggled to attract a buyer but was finally also bought by the Salim Group in January 2017, and so may be developed soon. It is not known whether or not the company has negotiated with the community.

- PT Permata Nusa Mandiri is another Yasa family concession, however, in this case it is believed that no new buyer has come forward for the concession.

- PT Wira Antara and PT Daya Indah Nusantara, with concessions located in Jayapura and Sarmi regencies, belong to the Musim Mas Group. Although it has not formally abandoned the concessions, Musim Mas says it is committed to it’s no deforestation policy, which effectively rules out developing them. Two other Musim Mas group concessions were in the same situation, having been given forest release certificates in 2012 before the company ‘got ethical’, also in remote areas of the upper Mamberamo River valley. Therefore, at some point the same land may be made available to other plantation companies, if new permits haven’t already been issued by the local Bupati, which could eventually open up this whole great river basin to industrial agriculture. The forest estate status gave an important layer of protection that has now been stripped away.

- PT Visi Hijau Nusantara, PT Duta Visi Global and PT Wahana Agri Karya have permits for a long strip of land over 100km long along the Trans-Papua highway in Boven Digoel. They are still actively seeking the plantation business licence they need, with PT Wahana Agri Karya engaged in an EIA process for the second time. The owner of these three companies is believed to be Edi Yosfi (he owned the companies through his business PT Star Vyobros until 2012, after which time the shares were transferred to individuals thought to be his associates). This raises a particular concern because Yosfi is a high-ranking official in the National Mandate Party, the same party as Zulkifli Hasan, and known to have close links with him. (( For example, also in September 2014, Zulkifli Hasan and Edi Yosfi were the two PAN politicians who accompanied failed-vice presidential candidate Hatta Rajasa to a meeting with the newly elected Joko Widodo: https://news.detik.com/berita/2845847/hatta-saya-bertemu-jokowi-ditemani-zulkifli-dan-edi-yosfi ))

The flexibility of Indonesia’s primary forest permit moratorium

Since 2011, Indonesia has imposed a moratorium on new permits in areas designated as primary forests and peatlands. A new map of these areas is produced every six months. If a company objects to this designation, it will send a letter to the ministry saying that the forest in the concession is all secondary. When these appeals are accepted, the time between the company’s letter of complaint and the ministry’s approval of the change is usually around three to four weeks, which means it is highly unlikely that the ministry has organised a thorough ground survey in that time. In all probability someone just looks at a satellite image. These appeals by companies have become a regular occurrence which totally defeats the purpose of the moratorium, and also raises questions of corruption.

A separate branch of the Forestry Ministry conducts a land cover survey each year (again, using satellite images), and in almost all cases the land which was reclassified as secondary forest for the moratorium map is still shown as primary forest in those surveys.

Seven of the plantations which got the forest release permit in September 2014 had previously successfully applied to remove land from the moratorium area. In November 2013, when the fifth iteration of the moratorium map was published, land marked as primary forest had been taken out of the moratorium area in the concessions of PT Visi Hijau Nusantara, PT Wahana Agri Karya, PT Duta Visi Global, PT Tunas Sawaerma, PT Wira Antara and PT Daya Indah Nusantara. Primary forest in PT Tunas Agung Sejahtera’s concession was excised from the map on its sixth iteration in May 2014.

The peat land in PT Tunas Sawaerma’s concession was not removed from the moratorium map, but Zulkifli Hasan gave the company the land release permit anyway (see above).

Primary forest is also found in PT Berkat Cipta Abadi’s concession, but it wasn’t part of the area moratorium because it already held some permits when the moratorium was introduced in 2011. The primary forest in PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa’s concession was released unintentionally due to the wrong map being published, as explained above.

If plantations are not developed.

The areas released from the forest estate in September 2014 add to a growing area of land with valuable forest cover, including primary forest, which are now outside the forest estate. This includes concessions which are not being developed because companies subsequently adopted no-deforestation policies, including concessions owned by Sinar Mas and Musim Mas.

Several other concessions have simply not been developed by the companies that acquired them, including five of the seven concessions in Boven Digoel formerly owned by the Menara Group and sold to Tadmax and Pacific Inter-link, which are also overwhelmingly composed of primary forest, and with many permit irregularities.

If the current permit holders fail to develop plantations on land released from the forest estate, it is still at risk. These ‘other use areas’ (Areal Penggunaan Lain) are very attractive to new investors because they only need the consent of local and provincial governments, and the land is often already designated as plantation land within the spatial plan.

There is also a new threat from the central government’s agraian reform policy. Jokowi had called in the 2015 National Medium-Term Development Plan for 9 million hectares of land to be included in an agrarian reform programme. 4.1 million hectares of this would come from the forest estate, or land recently released from it. In April 2017, the forestry and environment ministry drew up the initial map of these areas. Twenty percent of all land released from the forest estate is marked for inclusion in the agrarian reform programme, whether the plantations that originally obtained those release permits are developed or not.

On Indonesia’s crowded western islands, especially Sumatra and Java, agrarian reform is a much-needed step forward which peasant movements have fought for over many years. But in Papua the situation is very different. Indigenous Papuans still have land, unless it is taken from them by plantation companies. So who would benefit from agrarian reform in Papua? Is it a pretext for vast new transmigration policies, further marginalising indigenous Papuans?

Even if the current permit-holders do not manage to develop plantations, the decisions made by Zulkifli Hasan in September 2014 have made it much more likely that these important forest areas will be deforested at some point in the future. In combination with other stages in the dysfunctional permit system – location permits sold by bupatis to finance their re-election campaigns, worthless environmental impact assessments, and manipulative, divisive coercive methods to acquire land from its indigenous owners – this sort of lazy, careless (or possibly corrupt) approach to managing the forest estate can only lead to Papua’s forest being gradually eaten away by the plantation industry.