Mungkin kisah PT Menara Group di Aru telah usai, sekarang saatnya untuk melihat ke Boven Digoel. Disana terdapat rencana proyek mega perkebunan yang mempersilahkan masuk penguasa kayu Malaysia, yang menggunakan dalih pembenaran perkebunan sawit untuk mendapatkan sekitar 400.000 hektar lahan hutan primer.

Mungkin kisah PT Menara Group di Aru telah usai, sekarang saatnya untuk melihat ke Boven Digoel. Disana terdapat rencana proyek mega perkebunan yang mempersilahkan masuk penguasa kayu Malaysia, yang menggunakan dalih pembenaran perkebunan sawit untuk mendapatkan sekitar 400.000 hektar lahan hutan primer.

Masyarakat di kepulauan Aru sudah berhasil mengusir Grup Menara yang hendak mengklaim sekitar 500.000 hektar dari 629.000 hektar lahan demi perkebunan tebu. Setelah kuatnya perlawanan lokal, disokong oleh dukungan dari para aktivis di Ambon, Menteri Kehutanan, Zulfikli Hasan menyampaikan ke media massa pada 10 April lalu bahwa ia tidak akan menandatangani izin pelepasan kawasan hutan untuk Menara Group.

Pernyataan ini terjadi setelah kampanye “Save Aru” membuka kebobrokan tentang bagaimana upaya proses masuknya Menara Group ke kepulauan Aru: Mengapa rencana tata ruang Aru berubah secara dramatis dengan memperbolehkan perkebunan luas seperti itu? Mengapa izin diberikan walaupun kondisi yang layak tak terpenuhi? Mengapa Analisa Dampak Lingkungan (AMDAL) disetujui tanpa dilengkapinya deskripsi rencana perusahaan maupun syarat-syarat penting lainnya terkait dampak lingkungan? Sebagai respon atas tekanan dari masyarakat, baik Gubernur terpilih baru Maluku maupun Unit Kerja Presiden bidang Pengawasan dan Pengendalian Pembangunan (UKP4) mengatakan bahwa mereka akan melihat kembali prosesnya.

Para aktivis di Aru mengerti bahwa Menara Group masih bisa melakukan upaya untuk datang kembali, dan ada banyak perusahaan lain yang mengantri untuk menggantikan posisi mereka, terutama Grup Nusa Ina. Masa depan jangka panjang pulau Aru belumlah terjamin. Tapi ini adalah kabar baik.

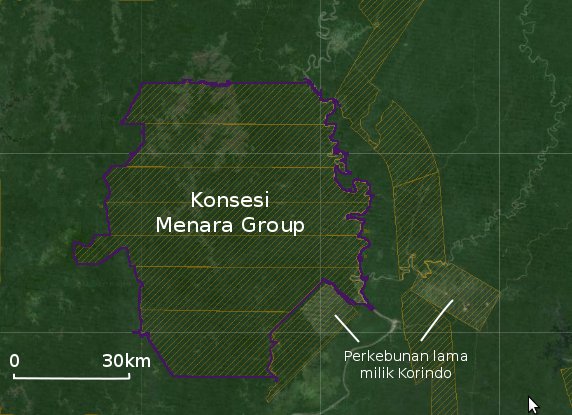

Namun hal ini tidak berarti bahwa Menara Group sudah keluar dari sektor perkebunan. Lepas dari upaya berujung nasib buruk di Aru, mereka juga telah berusaha untuk mendapatkan lahan luas di tanah Papua, dan tampaknya upaya mereka lebih berhasil disana. Grup Menara masuk ke Kabupaten Boven Digoel di bagian Selatan Papua sekitar 1 tahun sebelum datang ke Aru, dan telah mendapatkan konsesi atas 400.000 hektar lahan kelapa sawit di sana, kebanyakan di Distrik Jair dan Mandobo.

Terdapat beberapa kemiripan antara situasi yang terjadi di pulau Aru dan Boven Digoel. Keduanya merupakan tanah yang luas – sebagai contoh Boven Digoel memiliki luas 2/3 dari Bali. Keduanya memiliki hutan primer yang mengandung kayu-kayu berharga yang tidak pernah ditebang. Keduanya sama-sama memiliki izin dari bupati yang saat ini dipenjara karena bersalah atas tuntutan korupsi meski kedua kasus ini tidak terkait langsung dengan Menara Group.

Sayangnya, tidak seperti di Aru, tidak ada gerakan sosial yang bangkit di Boven Digoel dalam menyikapi situasi ini, dan tidak adanya pemantauan atas pelanggaran-pelanggaran yang mungkin terjadi. Sangat sedikit informasi yang bisa diperoleh di sana. Satu-satunya laporan langsung datang pada tahun 2013, saat penduduk desa menghubungi seorang pendeta yang berasal dari daerah situ namun sekarang beliau bekerja di tempat lain. Ia menyampaikan keluhannya karena sebuah perusahaan bernama Menara Group telah melakukan kunjungan ke berbagai desa sambil membagi-bagikan beberapa miliar Rupiah. Penduduk tidak paham untuk apa uang itu. Mereka menyangka ini adalah upaya tipu daya agar penduduk desa menandatangani surat pelepasan hak atas tanah ulayat lalu mendapatkan imbalan uang tunai tersebut.

Jika tidak ada yang mengawasi perusahaan ini, bisa jadi kabar berikutnya

yang kita dengar muncul setelah mesin-mesin besar tiba dan penduduk desa

baru menyadari telah kehilangan hutan mereka. Sebelum hal ini terjadi,

berikut beberapa upaya untuk mengumpulkan beberapa hal yang kita sudah ketahui tentang tanah dan perusahan yang terlibat di dalamnya.

Siapa dan Apakah Menara Group?

Menara Group tidak diketahui telah mengoperasikan perkebunan apapun sebelum mereka memasuki Aru dan Boven Digoel. Namun tampaknya mereka sangat ambisius dengan berani mengajukan perkebunan jauh lebih besar daripada sejumlah perusahaan perkebunan mapan dalam beberapa tahun terakhir ini.

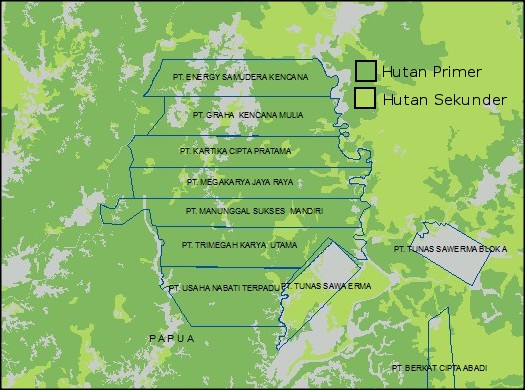

Batas luasan perkebunan di Papua adalah 40.000 hektar, hingga Menara Group

mendirikan 10 anak perusahaan, semuanya berlokasi di alamat yang berbeda di

daerah Grogol, Jakarta. Ternyata saat dikunjungi banyak dari alamat tersebut tidak eksis dan yang lain adalah ruko di mana pekerja toko tidak pernah dengar nama perusahan yang sepertinya beralamat di situ.

Ini adalah ciri khas Menara Group yang tampaknya telah melakukan banyak langkah untuk sembunyikan informasi tentang bisnis mereka. Kita tahu presiden perusahaan, Chairul Anhar, adalah seorang pengusaha Indonesia yang memiliki kepentingan di Malaysia. Direkturnya lebih dikenal: Da’i Bachtiar, Duta Besar Indonesia untuk Malaysia pada tahun 2008-2012, dan sebelumnya adalah kepala polisi Indonesia (KAPOLRI), yang berarti bahwa ia adalah sosok yang berpengaruh. Sebelum terjun ke proyek mega perkebunan, kelompok itu diyakini memiliki keterlibatan dalam bidang konsultasi, perangkat lunak perbankan dan e-commerce. Tapi sebagai perusahaan swasta, portofolio lengkap kepentingan mereka tidak diketahui. Tidak diketahui juga dimana perusahaan tersebut mendapatkan modal untuk memulai usaha perkebunan dalam skala yang sangat besar ini

Sebuah teori terungkap; tujuan utama Menara Group adalah untuk memfasilitasi perusahaan-perusahaan Malaysia yang ingin masuk ke Papua, mereka menjual beberapa anak perusahaan setelah mendapatkan izin. Pada tahun 2011, Menara Group telah menjual dua anak perusahaannya; PT Manunggal Sukses Mandiri dan PT Trimegah Karya Utama pada korporasi Tadmax dari Malaysia, memberikan Tadmax kesempatan untuk mengembangkan perkebunan seluas 80.000 hektar. Sangat memungkinkan bahwa 160.000 hektar lainnya (atau empat anak perusahaan) telah dipindahtangankan ke Pacific Inter-link, perusahaan lainnya yang berbasis di Malaysia.

Tadmax, Jelas Diiming-imingi Kayu

eKesepakatan Tadmax mengungkap lebih banyak informasi mengenai rencana lahan daripada Menara Grup yang memilih untuk lebih tertutup. Karena Tadmax adalah perusahaan publik di Malaysia, maka mereka harus mempublikasikan rincian lebih lanjut dari transaksi dan rekening mereka.

eKesepakatan Tadmax mengungkap lebih banyak informasi mengenai rencana lahan daripada Menara Grup yang memilih untuk lebih tertutup. Karena Tadmax adalah perusahaan publik di Malaysia, maka mereka harus mempublikasikan rincian lebih lanjut dari transaksi dan rekening mereka.

Nota yang diterbitkan pada saat penjualan termasuk valuasi perusahaan . Para valuers (penilai) mencatat bahwa hutan di kedua bidang itu adalah ” hutan yang tidak terganggu ” (undisturbed forest), yang belum pernah ditebang kecuali untuk kebutuhan perladangan lokal oleh penduduk desa. Mereka membuat perkiraan nilai kayu dalam konsesi : 218.000.000 Ringgit (780 miliar Rupiah). Kemudian mereka mengerjakan nilai konsesi kelapa sawit, berdasarkan dengan perbandingan penjualan tanah lainnya di Indonesia, yang memberikan angka 69.000.000 Ringgit (247 Milliar Rupiah). Mereka beranggapan bahwa penawaran lahan lainnya tidak memiliki komponen kayu, sebagaimana kutipan “permintaan verbal kami dengan Dinas Perhutanan mengungkap bahwa adanya suatu kebiasaan pemerintah Indonesia yang hanya mengeluarkan Izin Lokasi atas lahan hutan sekunder dengan kayu yang meliputi kurang dari 30% luas wilayah”.

Ini artinya bahwa 75% dari nilai konsesi di Boven Digoel adalah dari ekstraksi kayu, dan hanya 25% berasal dari penanaman kelapa sawit. Selain itu, hal yang tidak wajar bagi hutan primer seperti ini untuk mendapatkan izin untuk perkebunan kelapa sawit. Apa maksud dan motivasi Menara Group atas sisa lahan sebesar 320.000 hektar? Lebih penting sawit atau kayu? Mungkin kita bisa ingat juga bahwa di konsesi Menara Group di kepulauan Aru hanya sebagian kecil yang pernah ditebang, sebagian besar masih mengandung kayu berharga?

Tadmax membeli setiap perusahaan sebesar 40 juta USD. Dalam setiap pernyataan perusahaan dan laporan pers terkait rencana mereka, Tadmax secara eksplisit menggambarkan kepemilikan mereka di Papua sebagai ‘hak kayu’. Sementara kelapa sawit yang mereka benar-benar mendapatkan izinnya, nyaris tidak disebutkan. Dalam Laporan Tahunan tahun 2012 ,Tadmax menyebutkan harapannya pada saat itu untuk “melanjutkan untuk melakukan ekstraksi kayu dan kemudian mendirikan pembibitan kelapa sawit (kalau perusahaan memutuskan untuk memulai di sektor ini) dimulai pada kuartal ke-4 tahun 2013 “. Dengan kata lain, perusahaan belum yakin mengenai penanaman kelapa sawit.

Tadmax memiliki izin kelapa sawit, tetapi tampaknya mereka belum berfikir banyak tentang kelapa sawit. Masalahnya adalah pemerintah Indonesia tidak memberikan izin tanpa bersyarat untuk menebang habis hutan primer seperti itu. Izin HPH mencakup kondisi pengelolaan hutan. Mereka mengharapkan sesuatu kembali – perkebunan kelapa sawit akan memberikan hasil kembali bagi negara selama puluhan tahun, sedangkan rencana Tadmax adalah untuk penebangan hutan dalam waktu enam tahun, meninggalkan tanah kosong di belakang setelah itu. Izin tebang kayu Tadmax terpaku pada Izin Pemanfaatan Kayu dimaksudkan sebagai izin tambahan untuk memungkinkan perusahaan untuk memasarkan kayu diperoleh dalam proses pembersihan lahan untuk perkebunan.

Tadmax adalah sebuah perusahaan dengan latar belakang di bidang kayu.Sebelumnya dikenal sebagai Wijaya Baru Global Bhd dan dimiliki oleh salah satu taipan kayu Sarawak Tiong Raja Sing, sebelum Major Anuar Adam membeli saham utamanya pada tahun 2011. Ketua Menara Group Da’i Bachtiar juga termasuk dalam dewan direksi hingga Februari 2014.

Joint Venture Komplek Kayu Terpadu

Pada Agustus 2012, Tadmax masuk ke dalam sebuah usaha patungan (joint venture) dengan beberapa perusahaan lain berkantor di Malaysia untuk beroperasi bersama di Boven Digoel. Nama usaha patungan Tulen Jayamas. Dalam kesepakatan antara perusahaan ini tidak disebut rencana usaha kelapa sawit, tujuan Joint Venture ini untuk membangun sebuah Komplek Kayu Terpadu (Integrated Timber Complex) “yang akan usahakan pengolahan kayu bulat dari tanah milik subyeknya menjadi kayu lapis, kayu gergaji, kayu serpih dan hasil kayu lainnya”

Tadmax memiliki saham hanya 14% dalam usaha patungan tersebut, ada empat perusahaan lain yang memegang sisanya. Saham terbesar (50.5%) dipegang perusahaan bernama Bumimas Raya Sdn Bhd. Saat menandatangani kesepakatan, perusahaan ini disebut ‘perusahaan tidur’ (dormant) namun dari alamatnya dan nama-nama pemegang sahamnya tampaknya ada hubungan erat dengan Shin Yang Group, salah satu perusahaan kayu terbesar di Sarawak.

.

25% sahamnya adalah usaha patungan yang dimiliki Pacific Inter-link, sebuah perusahaan manufaktur dan perdagangan milik konglomerat terbesar di Yaman, Hayal Saeed Anam Group, ternyata kantornya pun di Malaysia. Pacific Inter-link diduga sudah membeli atau sedang dalam proses membeli empat anak perusahaan Menara Group. Selama beberapa bulan webnya memberitahukan bahwa Pacific Inter-Link “dalam tahap lanjut mengakuisisi saham mayoritas (80%) dalam beberapa perusahaan Indonesia yang secara bersamaan diberi konsesi dan izin atas bank tanah seluas 160,000 ha”.

Sebagai perusahaan privat, Pacific Inter-link tidak punya kewajiban untuk melapor akusisi kepada umum, maka kami tidak tahu kalau transaksi sudah selesai. Dalam nota kesepakatan untuk membentuk usaha patungan tidak disebut sebagai eksplisit bahwa keterlibatan Pacific Inter-link terkait dengan pemasaran kayu yang ada di atas konsesi 160,000 hektar (yang juga merupakan hutan primer), namun hal ini sangat mungkin.

Berbeda dari Tadmax, kemungkinan besar Pacific Interlink punya niat untuk menanam kelapa sawit, karena kegiatan bisnis intinya adalah mengekspor minyak sawit dan produk hasil olahan minyak sawit,namun sampai saat ini belum memiliki perkebunan sendiri. Dalam beberapa tahun terakhir ada kecenderungan perusahaan pedagang komoditas minyak sawit membuka perkebunan untuk menjamin ‘supply chain’-nya. Di antara perusahaan perdagangan minyak sawit lainnya yang sedang berencana investasi di Tanah Papua ada Noble Group dan Tianjin Julong Group.

Shin Yang mungkin juga berminat menanam kelapa sawit di daerah Papua. Selain usaha kayu, Shin Yang juga memiliki Sarawak Oil Palms Berhad, yang memiliki beberapa perkebunan di Sarawak.

Perusahaan lain yang memiliki saham dalam joint venture adalah Al Salam Bank Bahrain (8%) dan Yakima Dijaya Sdn Bhd (2%). Pemilik Yakima Dijaya Sdn Bhd, Yee Ming Seng, dilaporkan terlibat di industri kayu di Papua sejak tahun 90-an.

Tadmax mau jual lagi

Pada awal 2014 muncul kabar dalam koran-koran Malaysia bahwa Tadmax selama ini sedang dalam situasi keuangan kurang bagus dan ingin menjual sahamnya pada dua mantan anak perusahaan Menara Group. Terdengar kabar katanya ingin fokus di Malaysia saja. Mereka optimis akan beruntung karena Ringgit Malaysia sekarang lebih tinggi daripada tahun 2011 lalu. Tapi mengapa Tadmax ingin menjual aset utamanya? Bisa jadi karena mereka sedang mengalami beberapa kesulitan untuk mulai beroperasi di Papua.

Dunia bisnis, apalagi bisnis perkebunan, selalu bercendurung penuh rahasia dengan banyak informasi disembunyikan, sehingga sangat sulit mengetahui siapa yang ada di belakang upaya mengeksplotasi kekayaan alam di Boven Digoel, begitu pula dengan rencana penggunaan lahan.

Yang diketahui secara pasti adalah jauh dari menara-menara korporat di Jakarta, Kuala Lumpur atau Miri, ada sepotong hutan primer seluas 400,000 hektar dibatasi Sungai Digoel di mana burung cenderawasih masih bisa melakukan tarian ritual untuk pasangannya dan di mana kanguru pohon dan kuskus masih bisa cari rumahnya di cabang pohon tinggi.

Hutan ini juga adalah tempat tinggal masyarakat suku Auyu yang memegang hak ulayat sebagai tanda warisan dari leluhurnya. Sudah banyak abad mereka tinggal di sana selaras dengan alam. Apakah orang Auyu siap untuk menghadapi pergolakan yang sangat keras dalam kehidupan mereka yang pasti akan datang kalau para pengusaha berhasil merealisasi investasinya? Apakah mereka sudah menyetujui rencana perusahaan setelah mendapatkan informasi netral dan tanpa intimidasi atau penipuan? Apakah mereka tahu apa rencana perusahaan-perusahaan ini di lahan mereka?

Di Aru, masyarakat desa cerita bahwa Menara Group tidak pernah turun ke desa untuk sosialisasikan rencana mereka. Di Boven Digoel, perusahaan apakah akan jadi lebih bertanggung jawab?