Several of the companies involved in MIFEE have already begun their operations on the ground. Companies connected to the Medco, Rajawali and Korindo groups have all been logging the forests to make way for their plantations. A prerequisite to commencing operations is to negotiate the right to use the land of local people. Given the vast profits which these companies stand to make, the track record so far is a shocking catalogue of deceit, broken promises and coercion.

Under Indonesian law, an indigenous community has a form of communal rights over land known as ulayat rights. What this actually entails is open to some interpretation as the concept of ulayat has been developed through various pieces of legislation, and there is no single law that defines the rights of indigenous communities.(43) A law (Perdasus) which was provided for in Papua’s Special Autonomy package should have given Papuan indigenous communities greater rights over their lands, but this law took several years to be issued and the end result was weak and confusing.(44) Currently in Papua it seems that companies have deemed it sufficient to compensate communities for the wood contained in the forest, and thus fulfil their obligations to release the ulayat rights. Therefore they offer no compensation for the loss of land, non-timber forest products, loss of livelihood or the rupture from their traditional ways of existence. The sums that are offered are pitiful, and what’s more, communities report being cheated and forced into accepting them.

Throughout the Merauke regency, indigenous Papuans are having their forest taken with no alternative way to sustain themselves in the long term. Compiling reports and testimony from different villages can reveal just how systematic this process is. Other trends can also be seen from the reports, for example conflicts have sprung up between clans, between villages, or between individuals who support and those who oppose the investors. It is also plain to see that confusion is widespread, as people want to protect their land and livelihood but don’t know if they really have any choice to reject the plans or not. In some cases villagers may feel foolish if they have failed to protect their heritage for future generations. The strongest message that comes out of village after village however, is that there is a widespread rejection of the MIFEE plan by local people. Refusals to sign over ulayat rights are common, and in certain places have been demonstrated through direct action.

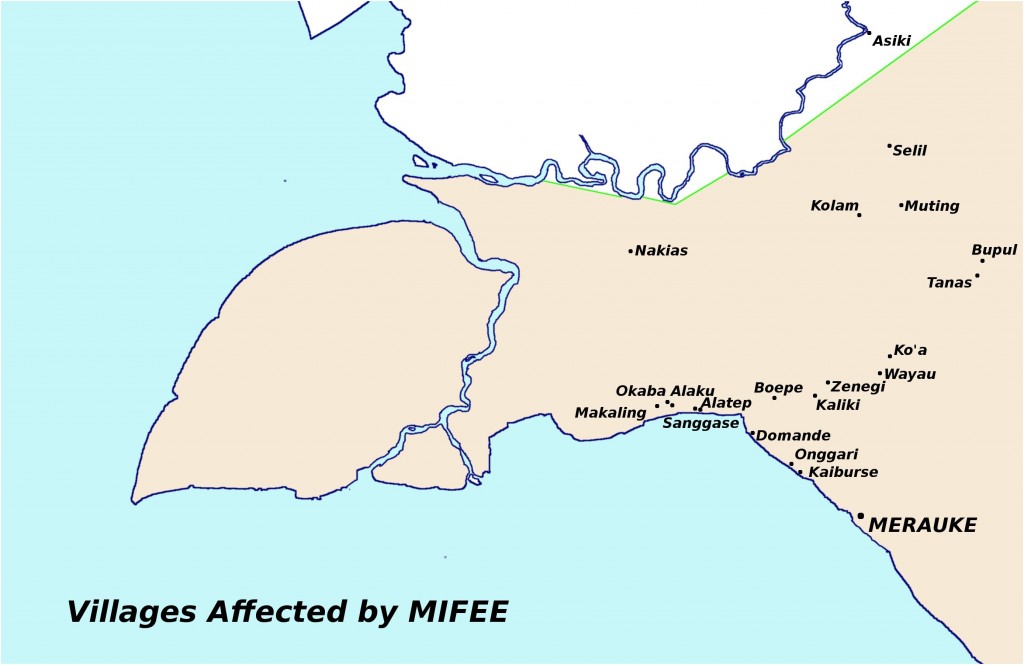

Information has been received about the following villages:

Kampung Zenegi, Medco Operational Area. Kampung Zenegi lies within the area in which Medco subsidiary PT Seleras Inti Semesta plans to develop its industrial forestry plantation. Medco’s approach to the village was deceitful: the company mounted a ceremony on 12th December 2009 in which it presented the village with what it termed a Certificate of Appreciation (Piagam Penghargaan). They also asked for the signatures of the village chief and leader of the village adat body on this document, and handed over 300 million Rupiah [$33,400].(45)

Several months later, in June 2010, conflict erupted when Medco attempted to remove wood that they had felled from the forests around this village. Local people were aggrieved because they felt there had been no discussion about how they were to be compensated for wood. Nor had the company fulfilled its promises to build a place of worship, a school, hire teachers or repair the road.

The people had regarded the money associated with the Certificate of Appreciation as a token of goodwill, and not as the compensation a company must pay for the wood they extract. But the company had a different point of view. According to them, the Certificate of Appreciation also had an appendix which they claimed had been discussed at the time. This appendix apparently includes an agreement that wood is to be compensated at a rate of 2000 Rupiah per cubic metre.

In the past, when the villagers have sold wood directly to wood traders, they are normally paid between 180,000 and 200,000 Rupiah per cubic metre. Aside from the deception, this agreement reveals that Medco believes its duty to compensate the community is only for the wood that grows on it. However Medco’s operation is more than just a logging concession. They intend to plant fast-growing trees which they can use in their chip mill, which means that local people will not be able to use the land for any other purpose. They are being dispossessed of their ancestral lands.

There are six clans in Zenegi village, and according to the Malind people’s customary beliefs, each clan is responsible for different pieces of land. Everybody knows which clan controls which area, and for a company to negotiate the surrender of ulayat rights, they must speak to the chief of each clan, not only the village chief.

A team from the NGO Pusaka conducted interviews in Zenegi to document the situation there for their book Beyond Malind Imagination. When they arrived they noted that a degree of conflict had sprung up between younger villagers and the elders who they felt had failed to protect their village. Some of the younger villagers later became the representatives in the village’s negotiations with the company. They have further complaints about the company’s actions. It had been agreed that the forest would be preserved in a radius of 2km around sacred sites, and the same for hunting grounds and sago forests. In fact the forest has been cut to within a radius of between 500 and 100 metres. The villagers also only gave their permission for wood to be extracted between 50 and 100 metres from the road, but it has been logged much further into the interior.(46)

Amongst the many promises made to the community was that they would engage experts, who would work together with US-based NGO Conservation International. This NGO has links with Medco – they carried out a land survey of Merauke for Medco, and Medco boss Arifin Panigoro has a seat on the NGO’s Business and Sustainability Council. Zenegi residents were told that the NGO would carry out a breeding program to make sure that wildlife populations would be maintained at the same levels as always. However, wildlife is starting to disappear. Local people report they have to go deeper into the forest to hunt, and a trader in deer meat from Merauke has also said that “obtaining venison from this village is no longer as easy as before”.

Medco has also showed that it is not averse to using violence. Emanuel Ndiken, a 22-year-old youth, was employed by PT Seleras Inti Semesta as a heavy machinery driver. He has claimed that he had been doing nothing more than requesting that his wages be paid on time and with a receipt. Because the company kept looking for excuses not to do this, he got angry and snapped at them. He was called to the office in August 2010. Curiously, the police who normally secured the location had returned to the city and had been replaced with soldiers. The soldiers struck Emanuel Ndiken until he lost consciousness. He related that he was bleeding from his nose, ears and eyes. When Pusaka next visited in November 2011 he was still suffering from disturbances to his sight, hearing and concentration, symptoms which have been confirmed by the local health clinic.

Kampung Boepe, Medco Operational Area. Kampung Boepe is the location of Medco subsidiary PT Medco Papua Industri Lestari’s wood-chip mill. The company agreed with the villagers to relocate them so they could build their factory on the site of their existing village, and plant seedlings on the surrounding land. The area now is restricted and local people cannot even enter. Meanwhile, the company has failed to provide new houses. The people have been forced to stay in other villages, and no longer have gardens. The compensation money they received was only enough to build new houses and eat during that time. The inhabitants of kampung Boepe were also deceived out of their land. A certificate to release the rights to customary land was signed, where the money was also referred to as ‘appreciation money’ (uang penghargaan). The sum paid was 100 million Rupiah for an area of 1000 hectares, which works out at 10 Rupiah per square metre [0.1 US cent].

Kampung Kaliki, Medco and Rajawali operational areas. The people of Kampung Kaliki’s traditional lands encompass areas of both Medco’s industrial forestry plantation and Rajawali’s sugar-cane plantation. The villagers told researchers from Pusaka that after seeing what had happened to their neighbours in Kampung Zenegi, they were determined to refuse MIFEE-style development. They resolved to question the ‘initial approaches’ which Medco had been making, which had taken the form of monthly payments to clan chiefs and teachers. Some of the chiefs, such as Agus Mahuze, who for five months had been signing a note of receipt left blank except for the amount of 500,000 Rupiah [$55], have decided to discontinue receiving the money.(47)

“The first time Medco came, they said they would provide development for the village, but actually all they have done is destroy the road we had before”, Vikaris, one of the villagers, told the Pusaka team when they conducted their research. They had also promised a housing development which had yet to materialise. Vikaris also said “Hopefully there are no traitors in this village. I am sure that the people of Kampung Kaliki do not want to sell their land. Village people know that selling their land means that they are selling their own mother. And no-one who sells their mother can live in peace. Because of that I am sure that not one hand’s width of land will be sold. Anyone who does this will continue to suffer. Because if today one hand’s width is sold, tomorrow it will be two hand’s width. Two hand’s widths lost will increase to become four hand’s widths. And then slowly but surely we will live in poverty on our own land.”(48)

Another report(49) tells of how conflict broke out amongst the clans as the people of Kaliki waited for the promised houses, as well as roads, motorbikes, schools and scholarships that were never forthcoming. Medco had made one agreement with four of the clans in the village, but made a separate agreement with the Gebze clan, to plant acacia on 20 hectares of land, for the disproportionate price of 20 million Rupiah [$2200]. This action caused resentment amongst the other clans, who were fighting amongst themselves while Medco continued undeterred. One member of the Gebze clan was believed to have been killed by black magic from another clan. When the church stepped in to resolve the conflict, the people united in their opposition to Medco. On the fifth of March 2011, the entire village announced their rejection of Medco, and said that they would use customary sanctions and measures against the company’s employees and representatives operating in Kaliki’s forest.(50)

The Rajawali Group has also approached the village several times seeking their approval for a sugar cane plantation. Meetings have been facilitated by the head of Kurik District, Martha Turupadang. On a meeting on the 7th February 2011, villagers had said they would only give their answer if a representative of the Merauke Catholic Presbytery could also be present at the meeting. But then Martha Turupadang denigrated the priest, and threatened the villagers that if they rejected the Rajawali group’s plans, she would cut off any funding to the village, and ensure that Kaliki community members would not receive treatment in the public hospital. Intimidated, villagers agreed to let Rajawali survey a limited area. The company ignored the agreement and instead surveyed the whole forest.

When Martha Turupadang returned to Kaliki at the start of March, seeking approval for Rajawali’s plans, she was accompanied by members of the police and military. On that visit, the former village head, who is in favour of Rajawali’s plans, reported that a group linked to the Catholic church had been running workshops in the village, and asked that they be barred from entering the village. The police chief responded by saying that since Kaliki people were Catholics, nobody could forbid the Catholic Church from visiting.(51)

Kampung Sanggase, Medco Operational Area. During 2011 a prolonged conflict has developed between the people of Kampung Sanggase, and their neighbours in Kampung Boepe and Medco. Local newspaper Tabloid Jubi has closely followed the developments which are connected to the Sanggase villagers’ demands for compensation.(52)

The conflict arose over which village had the ulayat rights over the 2800 hectare site that Medco was using for its wood-chip factory in kampung Boepe. The survey originally carried out by Conservation International for Medco claimed that the people of Boepe had ulayat rights over the land, and so the limited compensation that Medco paid was given to them. However four clans in Sanggase disputed that claim, saying that they owned the land, and the people of Boepe only had rights to use the land.

The first protest action, known as ‘tanam sasi‘, involved planting coconut, banana and sugar-cane in a ritual which normally takes place 40 days after someone’s death. After not getting a satisfactory response, on the 17th January Sanggase villagers used a pole to close off the entrance to Medco’s factory. This form of action, known as pemalangan, is quite common in Papua. Medco closed the factory until the dispute was resolved, and it appears from reports that it did not reopen for many months. The people were demanding compensation of 65 million Rupiah [$7200] for the land.

By April, tensions were running high. On 20th April, about 20 people from Sanggase, in traditional dress, came to PT Medco Papua’s offices to demand compensation. When there was no response, some of them invaded the offices, kicking and hitting the tables and doors and shouting curses at the company. At one point a leader of Medco was surrounded by angry villagers who refused to let him move, until he was rescued by police.

Negotiations proceeded, mediated by representatives of the local government and Customary Community Association (Lembaga Masyarakat Adat), until eventually the company offered to pay a sum of three billion rupiah, which was accepted by the people in a ceremony on 24th October 2011.

While the dispute with Medco was ongoing, villagers made clear their opposition to the planned operations of another company, PT Plasma Nutfah Marind Papua. That company is majority-owned by a Korean paper company, Moorim.(53)

Kampung Onggari, Rajawali operational area. Pusaka has related that during an participative mapping exercise involving several kampungs, villagers from Kampung Onggari discovered wooden stakes on their land, with yellow paint on top. One stake was marked ‘factory location’ with the initials of the company PT Cenderawasih Jaya Mandiri, a subsidiary of Rajawali. The villagers carrying out the survey were anxious about this, and they confirmed that they had never been involved in any discussions to give this land over to the government or any company.(54)

Kampung Domande, Rajawali operational area. Villagers in Domande agreed to be paid six billion rupiah [$660,000] compensation by Rajawali if they gave up their land. Within the first few days after the payment was made, traders from Merauke descended on the community to sell goods ranging from massage oils, to jeans, to motor bikes at up to 10–20 times the usual market price. Despite the fact that there’s no signal anywhere near the village, even mobile phones were sold. Most of the money has now been spent, leaving the villagers without land or compensation.(55)

Kampung Nakias, Dongin Prabhawa operational area. Pusaka has reported that local people have only been given 54 million Rupiah [$6000] as compensation for the wood that was taken from their land. This is far below its real value. In fact the level of compensation given to the ulayat holder when a company takes would has been stipulated by the provincial governor and should be 100,000 Rupiah per cubic metre of wood known as kayu indah, 50,000 rupiah for the merbau species, 10,000 Rupiah for non-merbau and 1000 Rupiah for fuel wood. Although local people signed for the money they received, they were not able to question Dongin Prabhawa’s calculations. The correct amount should almost certainly be much higher, as 5000 hectares of forest had been felled by June 2011. Villager Mariana Dinaulik has commented on this deal. “Is it just, that we only get this amount of compensation for the wood? The price cannot be compared to the people’s loss when their source of livelihood and food are taken away,” she said.(56)

Tabloid Jubi newspaper reported in December 2011 that people in PT Dongin Prabhawa’s area were being offered only 50,000 Rupiah for every hectare the company would use for its oil palm plantation. After people challenged this price, they were offered 90,000 Rupiah per hectare, but they do not consider that this is reasonable and they continue to refuse. Revd. Donald S. Mahuze, one of the ulayat holders, told the newspaper how the company has managed to cause divisions between clans.“We’ve been asking for 20 billion rupiahs compensation, but then we hear that some clans have accepted sums of around 650 million Rupiah. Then this attracts protests from other clans”, he said.(57)

News from other villages: The Justice and Peace Secretariat of Merauke’s Catholic Diocese invites villages from around the area to send in short reports about local village issues, which are then publicised online in Indonesian and English at their blog Sorak (short for Suara Orang Kampung – voice of the villagers). Here are some comments that they received from other villages. These indicate that several other investors related to MIFEE are continuing to push ahead with their development plans. As well as a widespread resolve to resist the plans, the accounts show that people are often also confused about what to do, as well as the signs of emerging conflict within communities that have been seen in some villages, quoted directly from the English version of the Sorak website:(58)

24 July 2011. I think that Customary Council in my village, Kampung Tanas, is good. Our elders are very supportive to defend our land since they themselves are the chiefs of the land. They are always tell us that our land is symbolized as our own mother. We are totally depend on the forest since we get our foods from the forest. If we sell the land, we sell our own mother.

Otniel Diwalek, Tanas Village Officer for Social Welfare.

26 July 2011. Local villagers in Alfasera now busy talking about new plan of expanding palm-oil plantation into their communal land and forest. According to local customary laws, the area is belongs to the people of Muting, Pahas, and Kolam. The issue is that part of them agreed and another part disagreed with the plan. Some villagers there told me that the number who have agreed is more than the disagreed one. I think, rather than disputing and fighting among ourselves, better we should sitting and talking together soon.

Pasifikus Anggojai, Bupul Villager.

28 August 2011. Big companies who have already operating in Muting area are: [1] PT. Bio Inti Agrindo, Registered No.8 in Merauke Regency Office by a Regent Decree dated 16 January 2007. They have 39,800 hectares of concession area and bought the land January 2007 from local communities at price of IDR 50.000 (about USD 6,0 –Ed.) per hectare. [2] PT. Papua Agro Lestari, Registered No.9 dated 16 January 2007 with concession area of 39,000 hectares. Also bought the land of local communities at same price. [3] PT. Berkat Cipta Abadi, Registered No.13 dated 16 January 2007 with concession area of 40,000 hectares. However, they cheat local people and said that they have only 14,000 hectares of concession area. They bought people’s land at price of Rp 70,000. We are not rejecting development since we also want prosperity but, if their investment methods continuously going that ways, nobody will welcome them. Really not make sense the price they have paid for our land and forests where is living thousands of big trees, high commercial woods and timbers, natural herb plants, animals, fishes. And now, after the companies already here, where have all those animals and plants gone?

Faustinus Ndiken, Muting Village.

22 October 2011. There is an investment plan on communal land of Alatep Community. The investor is PT. CGAB Development. They said that the company would clear the land for cassava, corn, and sugarcane plantation. The company had met twice with the local community in District Office in Okaba. At the time, they said that the company have a plan to use 20 hectares of land in Alaku site. I heard that the company now is preparing to present Environmental Impact Analysis (Analisis Dampak Lingkungan, AMDAL –Ed.). But, until today, there is no discussion about agreement or contract of the land. In previous meeting in the District Office, the company have promised to fund basic education of the local children of Alatep, build houses, church, clean water, electricity, and roads from the village to the planned site of plantation. Until now, not so clear yet how the plant would be implemented.

Obet Yawimahe, Head of Alatep Village, Okaba, Merauke.

29 November 2011 In last March 2011, we are the villagers of Kaiburse have met with the Head of Village and Elders Council to decide that we should reject presence of any investors such as PT. Rajawali in our customary lands. The meeting also attended by local government officials. When we allowing the company came into our customary land, where we can get our own livelihood? In the past, we have already give some part of our land to transmigration project and the government never paid us any compensation until today.

Christianus Y.Samkakai, Villagers of Kaiburse, Merauke.

5 December 2011. I have seen the situation of our brothers and sisters in Zanegi Village where is a company, PT. SIS, have operating. As the Chief of Wayau, I am really not want the similar situation happened in our own village. The company always promising many things but not proven at all. For example, they have promised to build new houses for Zanegi people but nothing happened until today. We are Marind people still living in traditional way of hunting and gathering. If we allow the companies to exploit our forests without any strict conditions and guarantees to be obeyed by them, our own life is really under serious threat to be extincted.

Edowardus Gebze, Chief of Wayau Village, District of Animha, Merauke.

5 December 2011. Recently, there is a company have a plan to start their operation in our village, Koa. The company is PT. Anugerah Rejeki Nusantara, a sugarcane estate company. The company have once came to us to explain their plan. They said that the sugarcane estate will implement a production-sharing scheme where is villagers would receive 20% while the company itself would get 30%. The company just lease or rent our land, not buy it. But, I have seen that they have already claimed some part of our traditional land. I have told to the Regent in Merauke Town and informed to him that decision to recieve or to reject the company plan is absolutely the rights of us, the villagers of Koa. Meanwhile, I heard another company, PT. Hardaya Group, was also prepared a plan to clear a huge land in our traditional territory. I heard it from one of the company’s employee. Until today, they still not came directly to us. We are the villagers of Koa should gathering together to discuss this issue.

Paulus W. Basik-Basik, Chairperson of Church Council, Koa Village, District of Animha, Merauke.

14 December 2011. On 9 August 2011, we have met with officials of PT. CGAD, a company who have offer us with a plan to exploit 20,000 hectares of our traditional forests. The area is covering 8 villages: Sanggase, Alateb, Alaku, Okaba, Makaling, Iwol, Dufmira, and Wambi. At the meeting, we are Makaling villagers have sharply reject the plan. Some District’s officials of Okaba are our witnesses in the meeting. Our reason to reject is our own human resource capacities is not prepared yet and, in fact, our village area is inside protected forests.

Martinus Aluen, Religious Leader of Makaling Village, District of Okaba, Merauke.

17 December 2011. There is a company have came to our village in Selil. The company is PT. Berkat Citra Abadi (BCA). In September 2010, the company came for the first time to explain their plan. They said they will come for further explanation and negotiation for two or three times more. They said they will cut our timber forests as wide as 31,000 hectares. They said they will pay us such as ‘agreement fee’ if we agreed with their plan. But, I don’t know how much the amount. Before, in February 2011, the company was actually have invited us, the villagers of Selil and Kindiki, to met in the District Office of Ulilin to receive the ‘agreement fee’ of IDR 50 millions (about USD 5,555 –Ed.). What I have knew is the fee was given to the villagers of Kindiki only. We are, the villagers of Selil, never received the money.

Nikolaus Renggam, Head of Public Administration Affairs, Village of Selil, Ulilin District, Merauke.

21 December 2011. We heard that some companies will come to our village, Selil. The companies are PT. Berkat Citra Abadi (BCA) and PT. Bio Inti Agrindo (BIA). They have plan to cut a huge are of our traditional forests, about 31,000 – 39,000 hectares. I myself and all of villagers of Selil not agreed yet with the companies. We are worried that we would face disasters like our brothers and sisters in the villages of Asike, Buepe, and Nakias who have previously agreed to permit the companies operating there. We are worried about the fate of our future generation: where are they will go when the forests already cleared? We are worried that they can not see anymore wild deers, casowaries, pigs and paradise birds since the forests already gone and remain just as a past history.

Linus Omba, Chief of Omba Clan, Selil Village, District of Ulilin, Merauke.

11 January 2012 In the Village of Koa, there is a company namely PT Hardaya Sugar Plantation want to invest on our ancestral land. Some officials of the company have came several times to meet with us but no agreements have been achieved so far. We are the people of Koa have agreed not to sell our ancestral land to the company. The land and the forest is sacred heritage from our ancestors and will be heritaged further to our children and grandchildren. If we sell the land to the company, our children and grandchildren will have no land anymore. If the land and the forest not belongs to us anymore, where we would get our foods?

Paulus Basik-basik, Villager of Koa, District of Animha, Merauke.

In addition to all this evidence of MIFEE’s social impacts that are already surfacing throughout the Merauke area, research by the Indonesian environmental NGO WALHI which visited Merauke in June 2011,estimated that at least 100,000 hectares of forest had been felled in the previous year alone.(59)