Three years ago, on August 11 2010, Agriculture Minister Suswono travelled to remote Kampung Serapu, inland from Merauke in the south-east corner of West Papua, He was there to launch the Merauke Integrated Food And Energy Estate(MIFEE). It was an ambitious plan for 1.28 million hectares of high-tech agribusiness development, with the aim of restoring Indonesia’s national self-sufficiency in rice and various basic food crops, bringing this vast untamed wilderness under the plough.

Of course, the land was not empty. Merauke is the home of the Malind-Anim, many of whom live in isolated villages deep in the forests or along the coastal plains, and an integral part of that forest system that provides for most of their needs, material and cultural. They have had to struggle to comprehend this inconceivably different fate that has been decided for them in distant offices, and in many cases, are having to learn to resist plans they know will devastate their livelihood.

Now MIFEE has reached its third birthday, although it is unlikely there were celebrations anywhere to mark the anniversary. Certainly not on the ground: the forests of Merauke only echo with worry as tragic stories of deception, intimidation, inter-community conflict, forest destruction and even starvation pass from village to village. MIFEE’s proponents are hardly satisfied either since development plans are advancing much more slowly than they hoped, and the Jakarta-based media has made it seem that by 2012 MIFEE was all but over: “MIFEE reduced by 80%”, “Food Estate moves to East Kalimantan”, the headlines have proclaimed.

After three years it is time for a progress check on MIFEE, and to set the record straight, because there is an awful lot of conflicting information out there. Different vested interests, pulling in different directions, have caused great confusion, and a lack of publicly available information hasn’t helped.

Agriculture minister Suswono’s latest public comment on the issue was in late July 2013. “MIFEE is still on” ((http://www.suarapembaruan.com/pages/e-paper/2013/07/27/files/assets/basic-html/page19.html)) , he said. Undeniably MIFEE is very much still alive and it is one of the most audacious land grabs currently taking place in Indonesia, possibly globally. It is just looking less and less like the high-tech rice estate Suswono promised.

The problem is Jakarta that is 3700km from Merauke, and so it has been possible for two quite different understandings of MIFEE to develop in parallel. People in Merauke, and others who are concerned with the fate of the forests and indigenous Papuans, look at the line of companies waiting to invest in the area and call that MIFEE. It includes some of the largest oil palm and industrial forestry plantations anywhere in Indonesia, as well as plenty of sugar cane. This plantation plan has come to represent MIFEE as it is being experienced in Merauke.

It is quite a contrast to the version of MIFEE which was envisaged in Jakarta, which required just as much land, if not more, but aimed to be more diverse, better managed and more productive than the typical plantations model. In this version the land would be divided into 5000 hectare bundles in ten integrated clusters, and developed in stages over twenty years. This version of MIFEE was designed as the answer to Indonesia’s shortfall in the production of basic foodstuffs such as rice, soya and sugar, large amounts of which are currently imported. MIFEE was to be Indonesia’s new rice granary. Jakarta’s version of MIFEE, being an ambitious and visionary plan, has been taken up as an important part of Indonesia’s development strategy.

Either way, the losers at the end of the day, of course, are the Malind people. Some might say it makes little difference if your ancestral forest is destroyed for paddy fields or for an oil palm plantation and course that’s true. Nevertheless, it is important to understand how these two parallel versions of MIFEE emerged, how they continue to coexist alongside one another, and crucially, how the image of MIFEE as a vital national food security project has continued to facilitate the start of Papua’s plantation explosion, without ever admitting that the two versions of the mega-project weren’t exactly the same thing. This essay will examine in some detail the parallel realities of MIFEE, together with some of the supporting policy that has been emerging over the last few years to support it and the wider paradigm of top-down development in West Papua.

MIFEE (Jakarta Version)

Wind the clock back to 2010. States and companies were buying up land all over the world in the wake of the 2008 food ‘crisis’ that had sent agricultural commodity prices soaring. A major land deal had just fallen through where Saudi investors had planned to buy up 500,000 hectares of Southern West Papua as part of a 1.9 million hectare ‘rice estate’. Local politicians were keen to find replacements. National politicians concurred – like many other countries, Indonesia had got caught up in the global panic wave of wanting to ensuring its future food security in an increasingly uncertain world. More immediately, Indonesia has for some time been dependent on imports for some key commodities such as rice and sugar, affecting its trade balance.

And so the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate was born. 1.28 million hectares were allocated for the plan, based on industrialised farming and modern management techniques. A map was drawn up with ten clusters, each with it’s own target crops and time-scale. Projected outputs for ‘food crops’ were even supplied: 1.95 million tons of rice, 2.02 million tons of maize, 167,000 tons of soya beans, beef from 64,000 cows . Oil palm and sugar cane were also part of the grand design, but limited to 20% and 30% of the total cultivated area respectively.

The MIFEE launched on August 11th 2010 was an ambitious plan, and several food and seed companies expressed their interest. State-owned enterprises said they were ready to get on board, supplying seeds and fertilizer, creating farmer-owned enterprises that could market by-products of rice cultivation and generate electricity from waste.

However, very swiftly there was no new news. There was some conflict with the Papuan provincial administration, which felt slighted by having been bypassed when MIFEE was created. Another obstacle was that it seemed like nobody wanted to foot the bill for the infrastructure development needed. What’s more, somewhat amazingly for such a major and complex development, no new body was set up to oversee MIFEE’s implementation. We could be forgiven for thinking that from the outset, no-one really had any intention to ever implement this MIFEE (Jakarta Version) at all.

MIFEE (Merauke Version)

Suswono travelled to Merauke in August 2010 to launch MIFEE, and was photographed shaking hands with the leader of Merauke Regency at the time, Johanes Gluba Gebze. Gluba Gebze smiled as he held a ribbon-wrapped copy of the MIFEE (Jakarta Version) Grand Design, but maybe he didn’t let on that he had other plans that might sabotage the food estate.

In the months of July and August 2010 at least 20 location permits were issued or renewed by Gluba Gebze’s local government. Only one of these permits was for food crops other than oil palm or sugar cane, but there were several industrial forestry permits. The location of these permits encompassed nearly all the land in Merauke Regency, except for a few protected areas, stretching far beyond the boundaries of the ten clusters allocated in the MIFEE (Jakarta Version) plan. Many of these permits were for the legal maximum size of 40,000 hectares each – in Papua plantations are permitted to be twice as big as elsewhere in Indonesia.

What could be the reason for this frenzy of permits? Well, in late August 2010 there were elections for a new regency leader. Gluba Gebze had already been in power for two full terms so he wasn’t eligible to stand, but had a favoured candidate that he hoped would help him with his ambition of creating a new province of South Papua and becoming the governor. Could the permits have bankrolled this election campaign? ((Gluba Gebze has been accused of corruption, although unrelated to the MIFEE project. He was arrested on 16th September 2013 under suspicion of Rp 18.5 billion (US$1.6 million) worth of corruption involving crocodile skin souvenirs.))

That candidate did not win the election, but it is these initial location permits, together with others issued before July 2010, that form the backbone of MIFEE (Merauke Version). In a sense this is the real MIFEE, because it is this onslaught of plantation development that the Malind people are currently having to deal with.

Which companies are investing in MIFEE?

The location permits given out by John Gluba Gebze are only the first stage in a legal process a company must follow before it can develop a new plantation. After that, an environmental impact assessment must be prepared and the forestry department must agree to release the land from the state forest estate. The company must also show that it has obtained the consent of indigenous landowners and compensated them for use of the land during the lifetime of the plantation, before it can apply for the final permit.

Faced with various obstacles, not all the companies have continued with their plans, but many have persevered, and so a huge amount of land continues to be under immediate threat.

Although the non-active concessions may of course be re-activated or reassigned, to look at the actual developments that are taking place right now gives a more accurate picture of how MIFEE is shaping up. So here’s the key data on plantation development in Merauke, as of August 2013, three years after MIFEE’s launch.

- Since 2007 around 80 initial location permits have been issued, but not all are being actively pursued. Somme permits have been revoked.

- At least twelve major corporate groups are actively trying to start new plantations, between them operating 24 subsidiary companies.

- Four corporate groups (Korindo, Daewoo International, Agro Mandiri Semesta and Central Cipta Murdaya) are developing eight oil palm plantations estimated to cover around 304,000 hectares.

- Six corporate groups (Wilmar, Rajawali, Astra Agro Lestari, Mayora, Medco and Central Cipta Murdaya) are investing in sugar cane, planning eleven plantations on land estimated at around 330,000 hectares.

- Between two and four companies wish to develop industrial forestry plantations, using up to 459,000 hectares. (including Medco and Texmaco which are definitely active, Moorim (status currently unclear) and newcomer PT Wahana Samudra Sentosa, which we don’t know much about yet)

- Only one company, the somewhat mysterious PT China Gate Agriculture Development is definitely interested in farming food crops other than oil palm and sugar cane. Its permit is for 20,000 hectares, which it will use for cassava Another company, PT Kharisma Agri Pratama, part of the Modern Group, is also reportedly still active in the area, although there has been no recent information to confirm this.

- That means that the grand total of land to be used in Merauke Regency, based on currently active companies only, can be estimated at 1,213,667 hectares. ((These figures are mostly based on the size of the initial location permits issued by the Merauke local government. Plantation permits (izin usaha perkebunan) are usually slightly smaller, but many companies have not obtained this permit yet and in other cases it’s size is unknown. Where IUP figures are available, they have been used in this calculation.))

| Company Name | Parent Company | Permit Size | Acquired land from customary owners? | Started Land clearing? |

| PT Berkat Citra Abadi | Korindo (possibly sold to Daewoo) | 40000 | Yes | Yes |

| PT Bio Inti Agrindo | Daewoo International | 39900 | Yes | Yes |

| PT Papua Agro Lestari | Daewoo International | 39800 | Yes | Yes |

| PT Dongin Prabhawa | Korindo | 39800 | Yes | Yes |

| PT Hardaya Sawit Papua | Central Cipta Murdaya | 31507 | Possibly | No |

| PT Central Cipta Murdaya | Central Cipta Murdaya | 40000 | Possibly | No |

| PT Agrinusa Persada Mulia | Agro Mandiri Semesta (Ganda Group) | 40000 | Yes | Yes |

| PT Agriprima Cipta Persada | Agro Mandiri Semesta (Ganda Group) | 33540 | Yes | |

| TOTAL OIL PALM | 304547 | |||

| PT Cenderawasih Jaya Mandiri | Rajawali Group | 22145 | Yes | Yes |

| PT Karya Bumi Papua | Rajawali Group | 22145 | Yes | Yes |

| PT Anugerah Rejeki Nusantara | Wilmar international | 27457 | Only a small amount | No |

| PT Lestari Subur Indonesia | Wilmar International | 40000 | No | No |

| PT Hardaya Sugar Papua | Central Cipta Murdaya | 44812 | No | No |

| PT Papua Daya Bio Energi | Medco Group | 13396 | No | For trial farm |

| PT Tebu Wahana Kreasi | Medco Group | 20282 | No | For trial farm |

| PT Dharma Agro Lestari | Astra Agro Lestari Group | 40000* | No | No |

| PT Randu Kuning Utama | Mayora Group | 40000* | No | No |

| PT Swarna Hijau Indah | Mayora Group | 30000* | No | No |

| PT Kurnia Alam Nusantara | Mayora Group | 30000* | No | No |

| TOTAL SUGAR-CANE | 330237* | |||

| PT Selaras Inti Semesta | Medco Group | 169000 | Yes | Yes |

| PT Merauke Rayon Jaya | Texmaco Group | 206800 | No | No |

| Wahana Samudera Sentosa | 79033 | No | No | |

| Plasma Nutfah Malind Papua | 64050 | No | No | |

| TOTAL INDUSTRIAL FORESTRY | 518883 | |||

| China Gate Agriculture Development | 20000 | No | No | |

| Kharisma Agri Pratama | 40000 | No | No | |

| FOOD CROPS | 60000 | |||

| TOTAL | 1213667 |

* = estimated

Three years later, the impacts of these plantations are being felt. Local people complain that they have been tricked out of their land, compensation has been inadequate, conflicts have emerged between local people, ancient forests and other ecosystems have been destroyed, sago groves damaged, forest animals have become hard to find, people have experienced hunger and children have even died of malnutrition, rivers and swamps have been polluted, military presence has increased, people resisting companies have been threatened as separatists, local people cannot get work with the companies or work for low wages and without contracts, companies break their promises to build community facilities. These impacts are explored in greater depth in Three Years of MIFEE – part 2.

This is only the beginning… of the twenty-four companies holding permits, only eight companies have started land clearing or planting. It is believed that fourteen have yet to start paying for land. That means a lot of the worst impacts have yet to be felt.

The graphic details.

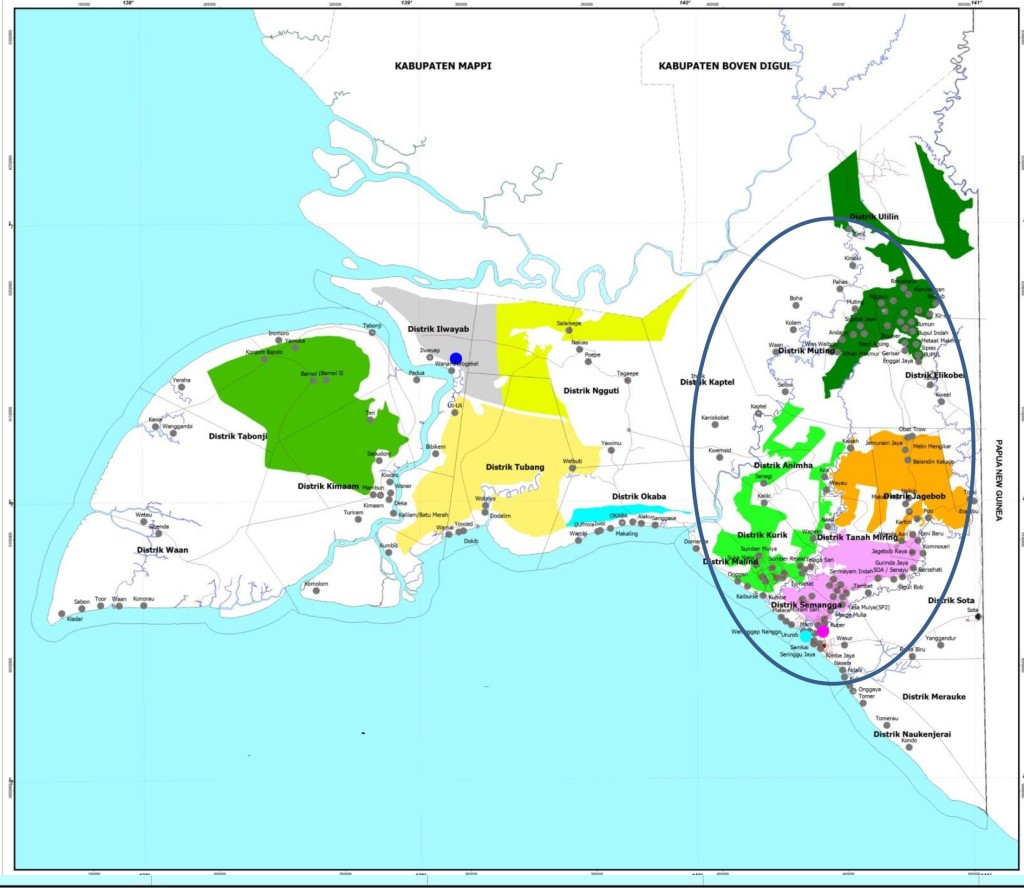

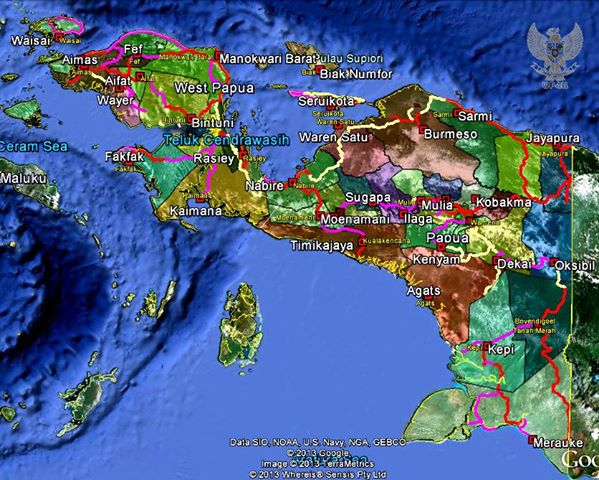

Map 1: MIFEE as seen from Jakarta

To help visualise the different plans for Merauke, here are a selection of maps which indicate where the two plans fit together and where they diverge. You can click on them to see them as big as we can make them, because unfortunately we don’t have access to higher-resolution versions. First of all, here is a map of MIFEE as envisaged by Jakarta, showing the clusters which were designed to be centres for food production. This recent version has changed slightly from the one published in the original MIFEE grand design.

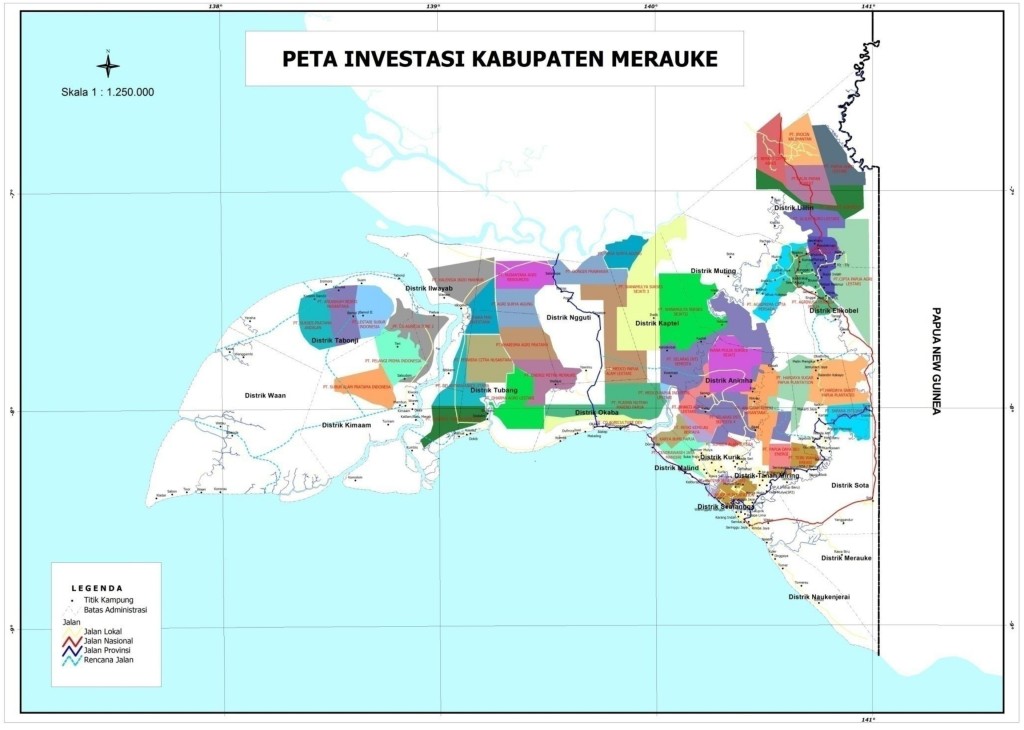

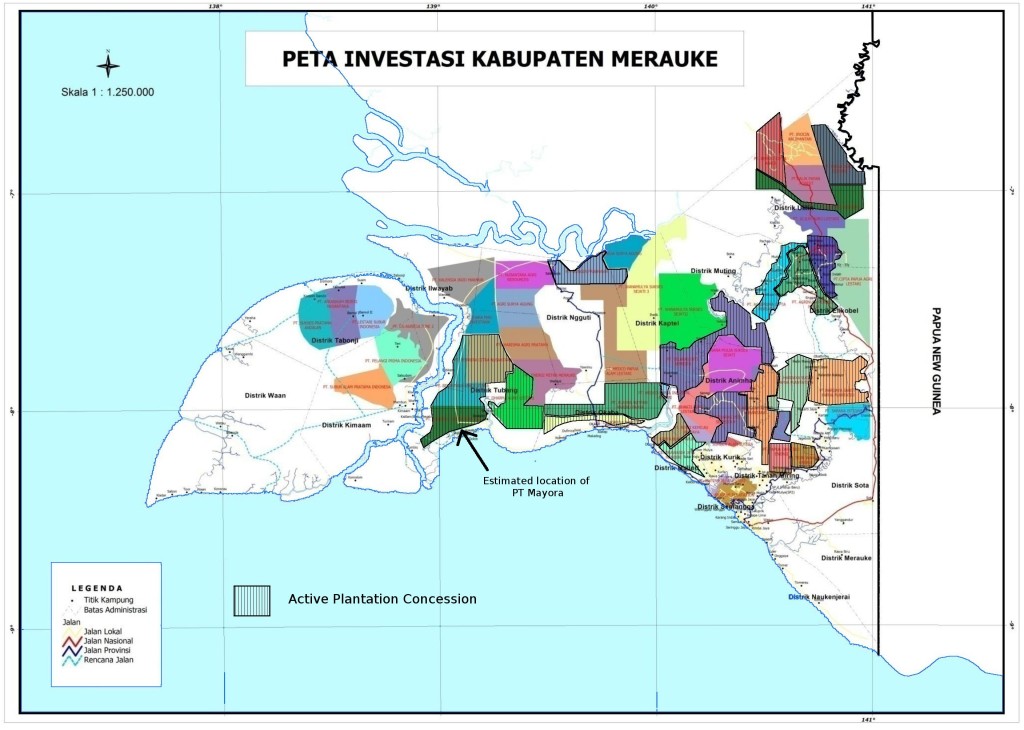

Map 2: Permits for Plantations

The next map is the latest version we have available of the map of location permits given to investors, produced by the Merauke local government. It is undated, but is probably about a year old. That means there are a few permits which are not shown: three subsidiaries of the Mayora Group, Wilmar subsidiary, PT Lestari Subur Indonesia and forestry company PT Wahana Samudra Sentosa. Texmaco is also not shown as that company is trying to start an industrial timber plantation based on old permits obtained from the national government.

Well, to look at that map it doesn’t seem like there is going to be any forest left at all! That is the result of John Gluba Gebze’s permit bonanza in 2010. At the time, the big white hole in the centre of the map in Ngguti District was occupied by Kertas Nusantara’s forestry permit. Texmaco would be in the North-Eastern white area, in Muting and Ulilin Districts. The only other white areas on the map, which have not been allocated for plantations are designated conservation forests.

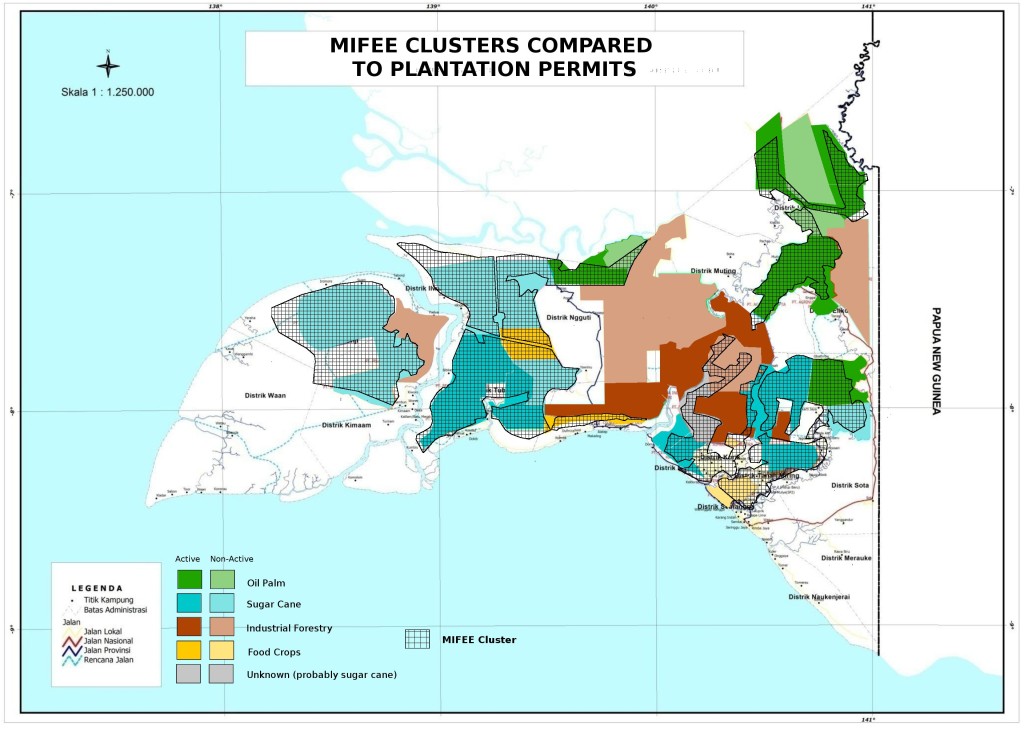

Map 3 Which areas are currently under threat from plantations?

As we know, not all those companies are not moving forward with their investments. To give an indication of which land is most directly under threat the following map shows the plantations concessions where it is known the companies are still active on the ground, or pursuing the additional permits they need before they can start planting. Mayora’s location is estimated based on reports of the areas the company is not active. Texmaco and PT Wahana Samudra Sentosa are not shown on this map, as there is insufficient data about the location of their concessions.

Map 4: How oil palm and sugar cane plantations have overtaken the food estate plan.

How do the maps match up? First of all, let’s take a look at the clusters allocated for the food and energy estate super-imposed on a map of the plantation permits. The MIFEE clusters are hatched and the areas covered by plantation permits are coloured. Areas allocated to oil palm plantations are shown in green, sugar cane in blue, other food crops in yellow and industrial forestry in brown. A darker colour indicates the company is currently active.

From this map you can see that permits for oil palm and sugar cane plantations (and the two possible food-crop plantations) occupy almost the whole area allocated for MIFEE. These plantation permits actually cover a larger area, extending beyond the boundaries of the clusters in many areas. Because there is almost no space left, to allocate land for other crops, such as large-scale rice or corn cultivation, local government would need to revoke oil palm or sugar-cane permits.

On the other hand, in almost all cases, industrial forestry plantations are outside the MIFEE clusters.

An important implication of this is that all the past and present planned industrial forestry plantations in Merauke should be considered as additional to MIFEE. All of the various government estimates of the size of MIFEE over the years do not include these forestry concessions, even if the timber is destined to be burnt as an energy source, as is the case with Medco’s plantation.

Between the two major groupings of MIFEE clusters there is a huge swathe of forest that appears to have been set aside for industrial forestry. At present some of the big forestry concession holders are not active, but there appear to be few barriers that would stop others moving in. As Merauke becomes increasingly developed and infrastructure improves, this land could be an attractive proposition for industrial forestry companies. Which means that in the long term, there really could be no forest left.

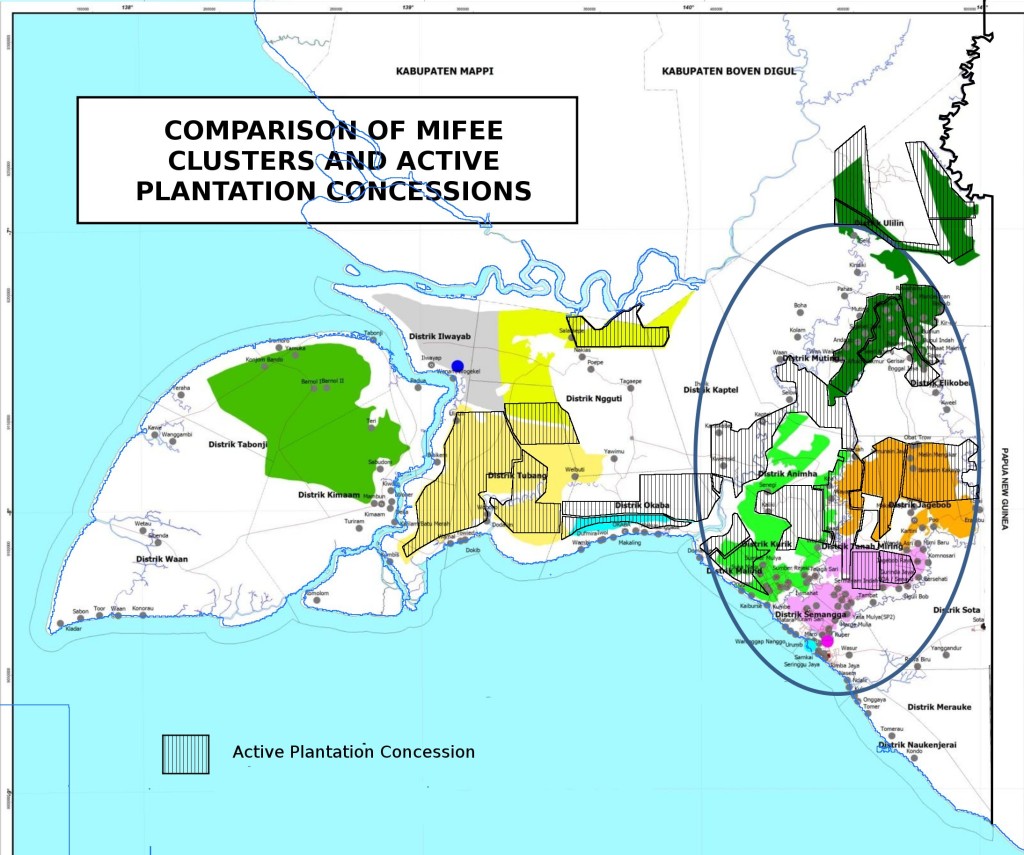

Map 5: A closer look at currently-active plantation companies within the MIFEE area.

By looking at the plantation companies which are still actively following the bureaucratic steps necessary to start operations within MIFEE clusters we can get an idea of how much land is actually available for agricultural development. This will indicate whether the cultivation of food crops (excluding sugar cane and oil palm) is still a viable possibility in Merauke – ie, MIFEE as it was originally envisaged. To illustrate this, the map of MIFEE clusters is the base, with hatched outlines of the plantations overlaid. Only active plantations are shown:

What does that show us? The most striking thing is that after all the plantations have taken their share, there is not so much land left for MIFEE’s food crops plan within the clusters! Even only taking into account the active companies, Remember, oil palm and sugar cane are supposed to be limited to 50% of the area between them. The four clusters inside the oval are the ones to be developed in the short term.

|

Intended in MIFEE |

Actual Situation |

|

| Cluster 1 |

Dry and wet rice cultivation, corn. |

40% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (65% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) There is a sizeable chunk of sugar-cane in the Northern part, but there is still some unallocated land. However, the map doesn’t show land which is already owned and cultivated mostly by transmigrant farmers near to Merauke. |

|

Cluster 2 |

Sugar cane, livestock, corn, ground nut and soya beans |

30% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (80% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) Rajawali’s sugar plantations eat up a substantial chunk, and Wilmar is in there too. There are also two plantations which are not listed as active but take up most of the rest of the space (PT Bhakti Agro Lestari and PT Reski Kemilau Berjaya) in this cluster. |

|

Cluster 3 |

Corn, ground nut, soybean, fruits and livestock |

80% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (90% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) Already almost entirely assigned to sugar and oil palm companies. |

|

Cluster 4 |

Ground nut, palm, fruits and livestock |

85% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (95% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) Nearly all allocated to oil palm companies, including the most northerly part around Selil which was originally supposed to be a different cluster, assigned for long term development. |

|

CLUSTERS FOR MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT (2015 -2019) |

||

|

Cluster 5 |

Rice and livestock |

80% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (80% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) Food crops, most likely cassava, fill almost all this small cluster, but from just one company |

|

Cluster 6 |

Fisheries, corn, sago and rice and livestock |

0% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (80% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) Still empty (although there are non-active permits for sugar cane) |

|

Cluster 7 |

Rice, sago and livestock |

55% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (95% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) Around half the area covered by companies trying to establish sugar-cane plantations |

|

Cluster 8 |

Livestock, rice and sago |

0% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (70% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) Still empty (although this area is now likely to become a conservation area) |

|

Cluster 9 |

Corn, ground nut, soybean, rice and livestock |

30% OCCUPIED BY ACTIVE PLANTATIONS (95% ALL PLANTATION PERMITS) A big chunk is already being developed for oil palm. |

The conclusion is that the scope for food agriculture inside the designated clusters has been severely reduced. Most of these plantation permits were given or renewed within a month of MIFEE’s inauguration ceremony, meaning that almost from day one it was impossible to imagine the scheme proceeding as planned.

It should have been clear three years ago that MIFEE would not be the food estate that would “feed Indonesia, then feed the world”. However since that time the image of a modern and integrated development project has consistently been used to justify new policies that impose a development model on West Papua that offers little that’s positive for the Papuan people, especially rural communities.

“MIFEE isn’t working”

As the promised plan for an integrated food and energy estate floundered, information emerging about MIFEE became increasingly confused and misleading. During 2011 and 2012 articles appeared in the mainstream media on a fairly regular basis, but they were rarely optimistic about the grand plans for Merauke. Some media outlets – notably Tempo magazine ((http://tapol.gn.apc.org/reports/120415_Tempo_report.pdf)) – did file reports on what was actually going on in Merauke – news of indigenous people being cheated out of their ancestral land. Most articles however, were based on gossip overheard in government and business circles in Jakarta, questions asked at press conferences and so on. These frustrated comments gave an impression that all was not well with the Jakarta version of MIFEE, but they gave a disjointed picture. Here’s a selection, in chronological order:

15/08/2011 “It has been two years since we floated the plan, but there has been no progress at all.” Suswono, the agriculture minister, proposing a new 200,000 hectare food estate in East Kalimantan as a substitute for MIFEE ((http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/archive/indonesia-turns-back-on-papua-food-bowl-plan/459493/))

26/08/2011 “The news is that the food estate has been postponed. The land that was available before will even be turned into protected forest ” Wilmar Commissioner MP Tumanggor – at that time Wilmar had been hoping for a 200,000 hectare plantation on Dolok Island. ((http://www.suarakarya-online.com/news.html?id=285764))

11/07/2012 “We were planning to have at least 1 million hectares of land, but then the land problems, such as trying to acquire customary land, occurred” Agriculture Ministry’s research and development agency chief, Haryono, saying that the land for MIFEE had been reduced to 200,000 hectares. ((http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/07/12/merauke-food-estate-land-likely-shrink-80.html))

The most frequently mentioned obstacles were the difficulties to obtain indigenous land, environmental impact assessments and permits at the provincial level. Almost invariably these news reports would be based on only one or two sources, were frequently contradictory and certainly were never backed up with maps or data which would give a more complete picture.

These articles created an impression that MIFEE was no longer a big deal, diverting attention away from what was actually happening in Merauke. Accounts of the size of MIFEE are a clear example. While land available for MIFEE was frequently reported as being reduced to 200,000 hectares or 228,000 hectares, this is misleading, as plantation companies have consistently been actively working on developing land several times that area. ((The figure of 228,000 hectares appears to have arisen for the first time in March 2011, as the amount of land that was apparently already free of any restrictions to do with indigenous ownership or forest status. The location of this 228,000 hectares has not been published. http://nasional.kompas.com/read/2011/03/30/03520963 ))

How the food estate myth continues to open the door for plantation development.

All the evidence seems to suggest that MIFEE (the Jakarta Version) has never really got off the ground while MIFEE is alive and kicking. It may seem slightly irrelevant to dwell too much on how and why this occurred. After all, to the dispossessed Malind people, does it really matter if their land was grabbed to make a rice farm or to make a plantation of acacia trees.? Maybe, maybe not. However, the story does not stop there.

The problem is, although MIFEE (Jakarta Version) is currently not much in evidence in Merauke, Jakarta has been reluctant to give up on the idea. Indeed it has become one of the cornerstones of a new national economic strategy and a repositioning of Indonesia’s approach to a troublesome Papua, both driven by the imperative to identify and remove barriers to growth and investment.

This is why Indonesia has been determined to maintain the myth of a modern, integrated project which is vital to national development. However as the government rolls out legislation, infrastructure and incentives to support that slightly fictional project, it is actually the plantation companies awarded permits by John Gluba Gebze that stand to benefit. The myth needs to be maintained – an integrated food project is much easier to justify than the more truthful version, where yet more forest is destroyed for oil palm and industrial forestry. The two versions of MIFEE are locked in an embrace which keeps opening doors to the destruction of Papuan forests.

Masterplan for the Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia’s Economic Development (MP3EI)

In May 2011 Indonesia launched a two hundred page document outlining its national economic strategy up to 2025. It is an ambitious plan, aiming to place Indonesia within the world’s ten largest economies by 2025. However in many ways it is far from revolutionary, mostly concentrating on consolidating Indonesia’s existing economic strengths. That means the island of Java is to be further industrialised, while the focus for the rest of the archipelago is to a large extent only extractive and resource industries – mining, plantations and fisheries, albeit with some additional downstream processing to add value. Papua is grouped with Maluku into one of six ‘economic corrridors’ and the key economic activities are copper mining (centred on the Freeport mine in Timika), oil and gas (around Bintuni bay, with a research and development centre in Sorong), nickel mining (in Halmahera, North Maluku) and industrial fisheries (based out of Ambon and Sofifi in Maluku) as well as MIFEE (the Jakarta Version) (obviously).

The information about MIFEE in the document was lifted straight out of the grand design published almost a year previously, seemingly with little update. The map with the ten clusters was reproduced, disregarding the fact that Merauke was already crawling with companies planning their plantations across the boundaries of those carefully-designed clusters.

The importance of MIFEE to this national vision document is highlighted in the introduction which proclaims “With the implementation of MP3EI platform, Indonesia aims to position itself as one of the world’s main food suppliers ” Yet in the MP3EI document, aside from Merauke, the only other area designated for basic food production is in Sulawesi, and details are extremely scant about proposed developments there.

Discussion of MIFEE consumes several pages, but in common with the rest of the MP3EI document, there is no mention of how to tackle any social or environmental problems which might emerge. It is a typical top-down approach which assumes that these questions are not going to be ignored, but they are treated as details that can be worked out later – there is no need to address them in the big masterplan, and certainly no need to build an economic plan which takes people and the environment as its starting point. ((Indeed the only mention of local people is the need for “Socialization to the local community about the implementation and benefits of the MIFEE program for the welfare of the community”. The word ‘socialisation’ is commonly used in Indonesian but less so in English – it basically means presenting plans to the community. Clearly the philosophy is a long way distant from the principle of Free Prior and Informed Consent which should be a minimum benchmark for any proposal of development on indigenous land. Papua’s low population density is mentioned as an obstacle for development, but the impact potentially millions of new migrants would have on the local population and culture also goes unmentioned.))

With the inclusion of MIFEE in MP3EI, the food estate was placed firmly back on the political agenda. However, the remote forests of Merauke remain very distant from the land of the glossy reports, which continue to depict a vision of MIFEE that is divergent from the local reality.

MP3EI rescues the rice plan – somewhat.

The Indonesian government is making considerable efforts to ensure the success of MP3EI, and has formed a committee to make sure all the MP3EI’s recommendations are implemented. One of its key mandates is to ensure that the various projects continue to move forward. That means analysing where the barriers to each of the MP3EI projects are and removing them – the word they use is “debottlenecking”. The barriers could be regulations, bureaucracy, lack of infrastructure etc. The intention is that nothing can stand in the way of this particular kind of progress, to prove that MP3EI is “not just business as usual”.

What that means is that MIFEE, as one of the flagship projects in the national plan, and one of the only food agriculture projects, cannot be allowed to fail completely. The team which is assigned to seek out the ‘bottlenecks’ will have to continue to keep one eye focussed on Merauke. If it is the local indigenous landowners which prove to be a bottleneck, then it is within their mandate to find a solution that favours the investment plans.

The MP3EI implementation committee (KP3EI) has taken each of the planned industries and broken them down into individual projects. The aim is to achieve “groundbreaking” (to get started) on each of these projects and then monitor their progress. ((A fairly uninformative overview of the status of each project can be viewed on their website, www.kp3ei.go.id))

In Merauke, three infrastructure projects are named, Merauke port, the trans-Papua road running along the PNG border, and another road from Merauke to the north-west of the MIFEE area. As well as this there are also two agricultural projects listed. One is to build up agricultural capacity by optimising existing farmland and creating new paddy fields. The other: to develop MIFEE Cluster 1.

This is interesting because it reveals that non-plantation-based agricultural development is still being planned in Merauke. More data was provided by a representative of the agriculture ministry in a presentation on MIFEE to a workshop on MP3EI and low carbon growth organised by Indonesia’s REDD task force. Whilst also noting the progress of the plantation companies, the unnamed presenter gave data on how much land had been optimised and converted to paddy-fields since 2006. A significant increase was seen in 2011 and 2012 according to that data, (3100 hectares optimised and 3400 hectares converted in the two-year period). The list also includes irrigation work, farm roads built and machines bought. ((http://www.redd-indonesia.org/pdf/seminar/Merauke/04_Kementan_MIFEE.pdf)) Of course, this falls far short of MIFEE’s original target of optimising 123,540 ha and converting 299,711 hectares by 2014, but nevertheless it is not a negligible area.

An MP3EI progress report ((http://www.kp3ei.go.id/uploads_file/20130617095359.Bab%206%20Perkembangan%20Pelaksanaan%20MP3EI%20KE%20Papua-Maluku_16%20MEI.pdf)) was published in March 2013. It listed the four working areas which are the current focus in the Merauke area. They are:

- Speed up the establishment of a provincial land-use planning regulation in Papua.

- Speed up up the permissions process of environmental impact assessments

- Mapping indigenously owned ancestral land in connection with the MIFEE clusters

- Suggest infrastructure developments to support MIFEE

Once again, the language used clearly indicates that MIFEE must go ahead, and focusses on removing barriers to progress. The first point refers to the lack of a provincial level land-use law which has long been cited as a key reason why MIFEE doesn’t move forward, ever since the previous provincial governor decided in October 2010 that the province would not sanction any new large-scale permits before a comprehensive provincial land-use plan was approved. Environmental impact assessments also need approval at the provincial level. The third point seems particularly callous – inviting indigenous people to map their ancestral land just so that it can be taken away again straight away.

Importantly, if these obstacles can be removed, it will support the development of all forms of agribusiness, whether food estates, oil palm plantations or timber farms, and could potentially also facilitate agribusiness development elsewhere in West Papua.

MP3EI Demands New Laws

The final chapter of the MP3EI document deals with how the plan is to be implemented and includes a list of several new pieces of legislation which would need to be created to facilitate the national economic plan. A few were of relevance to MIFEE:

“Review Law and Government Regulations related to the application of communal land (tanah ulayat) as an investment component which will enable the land owners to gain higher economic benefits. (this review is needed to support the MIFEE program). ” (target December 2011)

“Issue regulations to encourage infrastructure development in the eastern part of Indonesia.” (target December 2011)

“Issue regulations regarding Forestry Moratorium. ” (target July 2011)

“Issue regulations regarding incentive/facilitation to accelerate investment in centres of agricultural production, animal husbandry, and fishery industries.” (target August 2011)

As with the infrastructure and project development, these targets for legislation are also monitored. An update on progress ((http://www.setkab.go.id/mp3ei-3938-27-regulasi-telah-diterbitkan-untuk-sukseskan-mp3ei.html)) was published on a government website in March 2012, checking off new laws and regulations against the targets in the MP3EI document. The first three of the points were marked as ‘resolved’. So let’s have a closer look at the laws they created:

Law on land in the public interest

Carefully worded to sound benign, the first point, supposedly to allow indigenous landowners to get greater benefit, has actually become a powerful piece of legislation that will allow the state to appropriate land all over the archipelago, regardless of whether people hold indigenous rights or not. The 2012 Law on the Supply of Land in the Public Interest, (UU 2 Tahun 2012) is actually a law to regulate the compulsory purchase of land for development projects. Those development projects include infrastructure (road, rail, ports, airports, electricity distribution), oil and gas, dams, nature reserves and national security and defence, amongst others. In other words, a law which could encourage rampant land-grabbing nationwide.

MIFEE was the justification for this law when it was mentioned in the MP3EI document. In Merauke however, it’s effects will be limited, because in the end, neither agriculture nor plantations make it on to the list of land uses which require compulsory purchase. It will only affect indigenous landowners whose land is wanted for infrastructure projects connected to MIFEE, especially ports and roads, whether they are state projects, or funded by private investors.

It is worth pointing out that this law was already being planned before the MP3EI report was published. Linking this controversial law which has little relevance to Merauke explicitly to the MIFEE project, and describing it in a way which makes it sound beneficial to indigenous people, is an interesting way to conceal its real purpose. It seems that this has been an example of using the pretext of supporting a supposedly vital food security project in order to push through an unpopular piece of legislation.

The Acceleration of Development in Papua and West Papua: UP4B

The second point on the list above, infrastructure development in the East of Indonesia, was dealt with in two Presidential Regulations issued in September 2011, which clearly also had the dual aim of weakening support for Papuan independence. Presidential Regulation 65 was a kind of action plan to ‘speed up development’ in the two Papuan provinces, and Presidential Regulation 66 set up the Unit for the Acceleration of Development in Papua and West Papua (UP4B), the institution that would oversee the implementation of that program.

The impetus for this new development program can clearly be seen as being linked to MIFEE and MP3EI. One of the nine development strategies outlined in Presidential Regulation 65 is to develop a “competitive economy by developing economic clusters in strategic zones with a focus on MP3EI’s Papua-Maluku corridor”. Merauke is one of six of these strategic zones, alongside Jayapura, Mimika, Biak, Manokwari and Sorong. Other relevant strategic aims include improving transportation and other infrastructure, improving functional links between the different levels of government and promoting development in accordance with local, regional and national land-use plans. All of these aims can be interpreted as gearing Papua up for more top-down development.

However, the UP4B’s mandate goes far beyond preparing Papua for MP3EI projects. Amongst its other aims are fixing the woeful neglect of Papua’s rural health and education services, affirmative action for ethnic Papuans through quotas for study outside Papua and in the military/police, mapping the sources of political and human rights problems and so on.

These two regulations cannot be seen only as an attempt to build up the West Papuan economy but also need to be understood in the context of West Papua’s political situation at the time. There had been a special autonomy law for ten years, but it was widely regarded as a failure. The Indonesian government and security forces had refused to respect or implement many important provisions of that law, and special autonomy funds had merely fertilized corruption amongst the Papuan political elite, hurting the general population in many ways.

Urban social movements were mobilising more and more effectively. While on one hand the West Papua National Committee was calling huge demonstrations in support of an independence referendum, the Papua Peace Network was promoting the idea of dialogue to address West Papua’s problems at a fundamental level. Even the Papuan People’s Council (MRP), a governmental body created by the special autonomy law, had voted to symbolically ‘return’ that law to the government as an utter failure. The West Papuan conflict was receiving more and more attention internationally, with growing public sympathy for the independence cause as news of human rights abuses circulated more widely.

Some kind of action was needed, and so the President, unwilling to bow to any demands for meaningful change which involved the Papuan people’s participation, unilaterally created the UP4B. This new unit seeks to rebuild trust in the Indonesian state by focusing on economic welfare – the idea being that economic development will make people forget about all historical and structural injustices they have experienced. Evidently this approach ignores all the many complex reasons for the problems in West Papua connected to politics, history, militarism, demographics, racism and so on.

UP4B aims to win Papuans over by promoting local development such as schools, clinics, food security programs and village enterprise, much of which is indeed sorely needed. But behind that mask of supposed social responsibility it is also promoting MP3EI’s top-down development agenda. All of this is delivered as decreed by Jakarta, and Papuan people at no time are given the opportunity to decide how they want to be ‘developed’.

In fact despite the image it projects as purely development-orientated, UP4B is an overtly political project. Its vision statement, just one sentence long, clearly states that it wants to make Papuans proud to be an integral part of the Indonesian nation. Unsurprisingly, there are few signs that the UP4B has been greeted with much enthusiasm by Papuan people.

When President SBY set up the UP4B, he also chose the man he wanted to do the job. Retired General Bambang Darmono headed Indonesia’s forces in Aceh from 2002-2005, in a conflict that the Indonesian Human Rights Commission has recently described as a gross human rights violation. ((http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/08/02/military-operation-aceh-was-gross-human-rights-violation.html)) The choice of a non-Papuan military man with experience of combating independence movements sends a strong message that this unit is only concerned with furthering Jakarta’s will in West Papua

UP4B and MIFEE.

The UP4B’s website has not had much to say about MIFEE, preferring to concentrate on the higher-propaganda-value stories of affirmative action and education programs. The unit has only posted one article describing a visit to an unnamed MIFEE oil palm plantation by a UP4B reporter. ((He observed local people working for the company, and shows a worryingly superficial understanding of indigenous people’s complex relationship with progress when he states that ‘of course’ they welcome the development as it has brought roads, meaning they don’t have to spend days walking to leave the area. However this information is from the company, he has not noted whether he actually spoke with any villagers. http://www.up4b.go.id/index.php/prioritas-p4b/8-ekonomi/item/227-puluhan-ribu-polybag-disulap-menjadi-kebun-kelapa-sawit))

Being image conscious is one reason why UP4B chooses to say little about controversial projects such as MIFEE. The unit is also not involved at the village level, it’s role is to create a favorable investment climate, so much of its work is unseen by the public. However, the unit was given a definite mandate to facilitate MIFEE when it was created. Details are given in two appendices to Presidential Regulation 65/2011 which make up the Action Plan. The first is a list of ‘quick wins’ to be implemented in 2011-2014 and includes 52 points connected to the MP3EI plan. In Merauke this includes:

- The trans-Papua road.

- Road from Kumb-Okaba-Nakias

- Road from Merauke – Muting

- Continue building ocean fishing port in Merauke

- Road from Okaba – Wambi

- Build a port at Bade (on Digul River)

- Build a port administration building in Merauke

- Optimise and extend agricultural land in Merauke regency

- Supply agricultural machinery (tractors, planters, reapers, threshers, mini-combines, water pumps

- Build 100m cargo wharf at Merauke port

- Develop fertilizer processing and biogas industries

- Develop educational support sector

- Provide capital for capacity building in the community and to develop investment

- Build a village breeding centre for beef cattle

- Build agribusiness terminals, warehousing and export ports at Serapuh and Wogikel

- Bridges over the Koloy and Hewa rivers, and the Inggun swamp

- Extend Merauke’s Mopah airport

The central government would foot the bill for all those developments.

The second appendix to Presidential Regulation 66 of 2012 is the Comprehensive Action Plan which is more general, mostly expanding on the UP4B’s strategic aims. MIFEE is in there of course, and the plan also includes providing incentives for investment in the strategic zones it identified, which include Merauke. There is also a plan to make Merauke a ‘minapolitan’ – a concept which Indonesia has developed which means applying the principles of integrated agribusiness to fisheries. This is an idea which has been on the table since before MIFEE was launched. ((http://www.kkp.go.id/index.php/arsip/c/2577/Minapolitan-di-Food-Estate-Merauke/?category_id=62))

It is not the UP4B itself that will carry out the points on this action plan. It’s mandate is as an overseer: to make sure Papua stays on track with the top-down development model that MP3EI has decreed. This nevertheless makes it a very powerful organisation designed to impose Jakarta’s vision for development on Papua, in Jakarta’s interest, and with virtually no participation from the people of Papua.

Presidential Regulation 40/2013: Military to build new roads.

Another piece of legislation, which the President decreed in May 2013, is also intended to support infrastructure development guided by MP3EI. Presidential Regulation 40/2013 allocates central funding for the construction of a network of roads across Papua. Most controversially, many of these roads are to be built by the military.

The road network (called Roads to Accelerate Development in Papua and West Papua or P4B) is clearly a product of the same thinking that produced MIFEE, MP3EI and the UP4B. The road network is clearly seen to follow the MP3EI corridor, building a frontier road from Merauke to Jayapura and then through the central highlands to access Nabire and Timika, passing near both the Freeport mine and the gold-rich areas of Paniai in the Western Highlands. Another road along the north coast passes Sarmi which is currently the site of oil and gas exploration, and on to the Bird’s Head peninsula where it meets the other oil and gas nodes in Bintuni Bay and Sorong. ((map sourced from http://zonadamai.wordpress.com/2013/06/03/inilah-ruas-jalan-strategis-nasional-papua-papua-barat-yang-akan-dibangun-tni-2/ ))

Around Merauke, the roads include the border road and roads connecting the coast to the north-west (Wanam) and northern (Nakias areas).

One of the most controversial aspects of Presidential Regulation 40/2013 is that about half of the roads will be built by the military. Those roads tend to be in mountainous areas where geographical conditions are difficult, or in zones prone to conflict. This increased military presence is greatly worrying as it can be expected to bring several problems. Even if outright violent conflict does not occur, it is inevitable that local people living close to the road-building areas will feel afraid and intimidated. The Indonesian military in Papua is also often accused of discriminatory and prejudiced behaviour toward local people, raping women (even when the soldiers believe the relationship is consensual, often indigenous women are just too scared of repercussion towards them or their community to refuse), running prostitution, gambling and alcohol businesses, illegal businesses selling wood, forest animals or forest products, and so on.

Announcing the new regulation, the deputy head of the UP4B Eduard Fontanaba said that the UP4B was involved in its design – indeed it had been struggling for around six months to bring it to fruition. ((http://www.up4b.go.id/index.php/prioritas-p4b/4-hukum-dan-ham/item/424-perpres-nomor-40-tahun-2013-solusi-membuka-isolasi-papua)) In other words, an institution led by a retired general has proposed bringing the army in to build roads to promote industrial development. The military stands to earn 425 billion Rupiah from the project. Whether this implies that the army is acting out of economic motives (to expand its business activities), or whether the plan is part of a political strategy to ensure the continuing militarisation of Papua, it is a clear sign that military might will play an important role in pushing forward development. ((http://www.up4b.go.id/index.php/berita/media-massa/item/570-tni-siap-bangun-14-ruas-jalan-di-papua-ksad-minta-tambahan-waktu ))

MIFEE Ploughs through the Forestry Moratorium.

In 2011 Indonesia made a deal with Norway where in exchange for US$ 1 billion, Indonesia would impose a moratorium on new permits to clear primary forest and peatland for two years. The reasoning was that Indonesia was effectively one of the highest contributors to climate change worldwide due to rampant deforestation, and a two year moratorium could break the pattern and allow a new paradigm of resource use to be developed.

After months of delay and uncertainty the moratorium was finally signed on 20th May 2011. By that time Indonesia had managed to negotiate several exceptions, for nationally important projects, in line with the MP3EI target industries. Land intended for rice and sugar cane cultivation was included as one of the exceptions, surely with a nod to MIFEE, and with the reasoning that Indonesia needed to ensure self-sufficiency in those two crops. In reality, MIFEE has effectively managed to squeeze more land out of the moratorium’s protection.

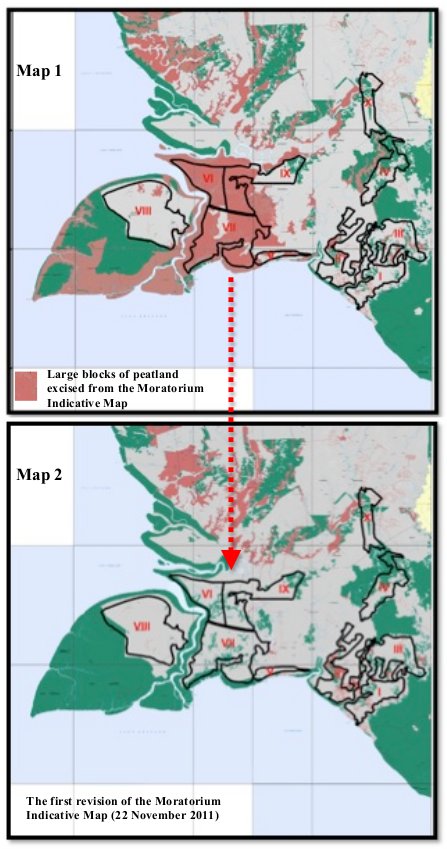

Every six months, the moratorium map has been updated. Around Merauke this means that huge swathes of land have been cut from the map and no longer enjoy this protection. The biggest cut was in the first revision. Most of the eastern part of the MIFEE area (clusters 5,6,7 and 9) are covered with peatland. The peat is not especially deep, data collected in 2001 estimated it as between 50-100 cm, but it is the second largest area of peatland in Papua, after the Asmat swamps. It is also mostly primary forest.

The area was marked as peatland on the original moratorium map, but by the time the first revision was published, the area was blank again. Greenomics highlighted the differences on a map. ((http://www.greenomics.org/docs/Report_201202_Merauke_Food_and_Energy_Estate.pdf))

The whole pink peat area has been cut from the moratorium! A lot of it was inside MIFEE clusters, or the other areas which have also got permits that border them to the east. It looks very much as if the map was altered to accommodate MIFEE, although the forestry service never gives explanations for why particular changes are made.

Given that Indonesia has insisted on exemptions for rice and sugar-cane, does this mean it is legitimate to cut the area from the map? According to the MIFEE (Jakarta Version) plan, the land was designated for mixed farming, including some rice, but also other crops which are not exempt from the moratorium. On the other hand, all the plantation permits which have been given in the area are for sugar cane, which does qualify for an exemption. Surely the proper procedure in such cases would be to allow permits to grow these exempted crops (rice or sugar cane), and withhold them for other crops, not just wipe it off the map entirely. If an area is excluded from the map completely then the government is free to give out permits for whichever use it pleases.

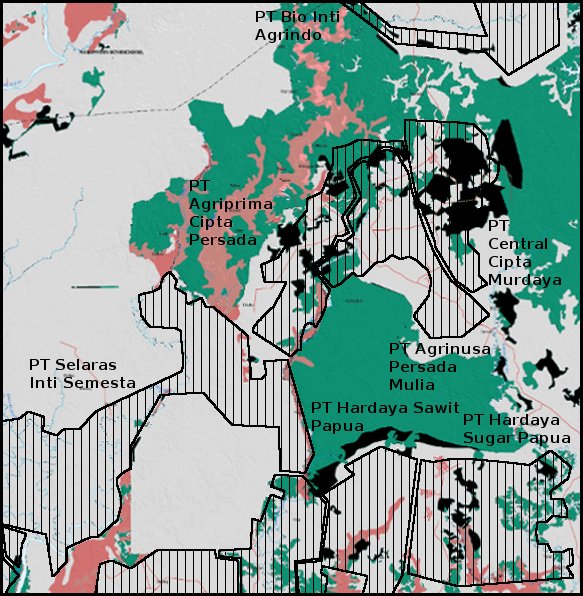

Oil palm is most certainly not eligible for an exception to the moratorium. But in a later revision of the moratorium map (the moratorium was renewed in 2013) several areas of primary forest have been excluded from the MIFEE clusters that are intended for oil palm. In the map below the black areas indicate land that has been excised from the moratorium map around MIFEE cluster 4. The map is overlaid with the oil palm permits that have already been issued. The map clearly shows that a considerable area of primary forest has been removed from the moratorium map. This includes about half of PT Central Cipta Murdaya’s concession, and smaller areas included in PT Agriprima Cipta Persada, PT Agrinusa Persada Mulia, PT Hardaya Sugar Papua and PT Hardaya Sawit Papua.

Opening new frontiers.

Could it ever have been possible in a few short years to convert a vast forested wilderness with virtually no infrastructure into a vibrant centre for high-tech agro-industry? A disciplined centrally-planned authoritarian state such as China might have managed it but in Indonesia it always seemed a bit implausible. But the act of presenting that dream has opened this frontier to the same crowd of logging and plantation companies that has already devastated Sumatra and Kalimantan. The food estate is still hanging on, but considerably less ambitious than originally planned

Maybe that is the nature of a frontier – first come the pioneers, whose crude methods carry risks but can bring high returns, and then more infrastructure-dependent enterprises move in when conditions are right. So maybe high-tech rice cultivation will make it to Merauke some day. Or maybe just more oil palm. One way or another, the Malind people are facing a severe upheaval to their traditional way of life, which as they well know, is unlikely to do them any good.