On 5th June 2018, the Mpur people of the Kebar valley, in Tambrauw Regency, Papua Barat Province, went to the worksite plantation company PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa as bulldozers were working and confronted the company it continued to clear their forest for an corn plantation.

On 5th June 2018, the Mpur people of the Kebar valley, in Tambrauw Regency, Papua Barat Province, went to the worksite plantation company PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa as bulldozers were working and confronted the company it continued to clear their forest for an corn plantation.

After an angry exchange of words they proceeded to the company’s field office, where the Ariks clan explained that they were going to return the money they had received from the company a few years before. Holding a package containing 100 million Rupiah, Semuel Ariks, representing the clan, informed company workers “We have already asked the company to stop working but the company continues to clear land. For this reason, we are taking back our customary land and we are returning the money.” (( Kami sudah minta perusahaan harus setop pekerjaan tetapi perusahaan tetap membongkar terus. Dengan demikian, tanah adat kami kami cabut kembali, dan uang kami kembalikan. ))

Nobody from the company was willing to accept the money, as doing so would weaken the company’s claim to use the land, so Semuel Ariks simply left it at the company office and departed with the rest of the indigenous people. The company passed the money to the local police, who have been encouraging the Ariks clan to take it back, but they have refused.

The Ariks clan were aware that in February this year the Arumi clan had also tried to return money to the company, 50 million Rupiah, but were obliged to bring the money back home after the company refused to accept it.

Neither of the clans, nor the four other landowning clans so far affected by PT BAPP’s 19368 hectare corn plantation, disputes having accepted money from the company. The problem, they claim, is that the company was not honest about its plans.

The first contact the clan leaders had with the company, was when they were summoned to a meeting in Arumi village. No-one is sure of the date, they think it was in 2015, although it may have been 2016. They waited until 3pm when the representatives finally showed up, and described their plan to plant corn in the Kebar valley.

Clan members allege they were told that the plans were for a two year trial study, and they believed it would only be on small grassland areas. At this stage the company had actually already planted an area of corn on grassland, after meeting with two administrative village heads. The representatives offered ‘tali asih’ money, a deliberately vague term often used by plantation companies in Papua which translates vaguely as ‘cords of friendship’, but which companies later claim represents a relinquishment of land rights by the indigenous recipients. The money offered was 50 or 100 million Rupiah per clan, all the clans accepted, and the representatives left the same afternoon.

None of the clans imagined that they had surrendered their rights to their ancestral land that day. They say that the information that they received was minimal and misleading. They weren’t even told the name of the company, the people who spoke at the meeting made it seem as if they were planning to implement a programme initiated by the Tambrauw Regency Agriculture Agency (Dinas Pertanian). At no point were they shown a map or asked to participate in an exercise to establish customary land boundaries. They were never given any copy of whatever documentation the company had taken away with them.

When the company moved beyond the grassland areas and started clearing forest and sago groves, people started to protest. They challenged the company out in the field, but had to abandon their protest after armed police and military showed up.

There are now around ten members of the Police Mobile Brigade (Brimob) tasked with protecting the company. The atmosphere of intimidation has meant that the local people are cautious in expressing their opposition to the plantation, but protests have continued.

People have appealed to the church to support them. After representatives of the Synod of the GKI (Evangelical Christian Church in Tanah Papua) managed to get documents from the company last year, they found out that it actually had a permit, issued by the local Bupati, for a 19368 hectare plantation which would stretch along the whole Kebar valley, over 40km from end to end.

It was also only after protesting that people realised that this project had nothing to do with the local government Agriculture Agency but was a private company named PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa. They then realised that this was the same company which had met them in 2014, in the sub-district office, to propose an oil palm plantation. They had emphatically rejected that proposal at the time.

From this story, it is very clear that this is a case of land-grabbing. The company has not engaged in a valid or sincere process of negotiation with the six clans, which Indonesian law recognises as the legitimate land rights holders on the land in question. Stories like these are commonplace in Papua, where companies routinely present any document they have persuaded indigenous leaders to sign as proof that the entire community has relinquished its collective rights to the land. Since the land law is full of ambiguities and lacking in specifics, it offers little formal protection for indigenous communities against these powerful and unscrupulous companies.

The people of Kebar are now calling for the company’s permits to be revoked. It turns out there are a series of serious irregularities in the permits which would mean this is entirely justified.

First of all, there is no environmental impact assessment. A preliminary framework was prepared in April 2016, but the process of discussing the final document has been suspended due to opposition. That means that there has been no evaluation of the environmental effects of a plantation on the ecological richness of the Kebar valley, a landscape like no other in Papua, being a mid-altitude mosaic of grasslands and marshes interspersed with forest, which could be expected to host unique ecological communities and possibly its own endemic species. Virtually the whole valley bottom is included in the permit area. There has been no evaluation of the impact to the two conservation areas of the Arfak and Tambrauw mountains which surround the valley, nor the effects of vast amounts of agricultural chemicals pouring into the headwaters of the Kamundan River, which flows for hundreds of kilometres through the forests and swamps of the Bird’s Head peninsula. There has been no study of the effects the introduction of industrial agriculture on the lives of the indigenous people of the Kebar valley, or a chance for them to have their say about the impacts.

The permit allowing the land to be released from the forest estate is also highly problematic. It was issued by former forestry minister Zulkifli Hasan on his last day in his job, 29th September 2014, when he seemed to be clearing his desk by signing all pending requests, in many cases without due care and attention. In this case, the decree he signed stated that of the 32390 hectares 13021 ha would not be released because it was primary forest, and therefore only 19368 ha would be released. However the accompanying map of the area showed the full 32390 hectares – somebody had made a mistake. This 13021 ha now has no state protection whatsoever.

Furthermore, the intended use in the 2014 forest release was explicitly stated as oil palm, yet the company has started planting corn. What appears to have happened, is that after it became apparent that there would be widespread opposition to an oil palm plantation, the company approached the Bupati of Tambrauw Regency, Gabriel Asem. On the 28th September 2015 he issued a location permit to the company (SK 521/296/2015), and then on the same day, issued a business licence for food crops (SK 521/297/2015).

Both permits were for 19,368 hectares, the area released from the forest estate by Zulkifli Hasan. However, the accompanying maps show that the company were aware of the former forestry minister’s mistake, since they do not include the primary forest areas.

Needless to say, this is not how the permit system is supposed to work. A location permit is issued first, valid for three years, so the company can go about trying to meet all the other requirements, including preparing an environmental impact assessment study for evaluation. After this has been completed, a business licence can be issued (the relevant legislation for Food Crops Business Licences is Agriculture Ministry Regulation 39/2010). According to the Forestry Ministry’s own regulations valid in September 2014 (Forestry Ministry Regulations 33/2010 and 28/2014), forest cannot be released unless the company possesses a business licence (and has therefore gone through the EIA process). However, Zulkifli Hasan routinely ignored his own regulations as he released over 900,000 hectares of Papua forest from the forest estate during his five year term of office.

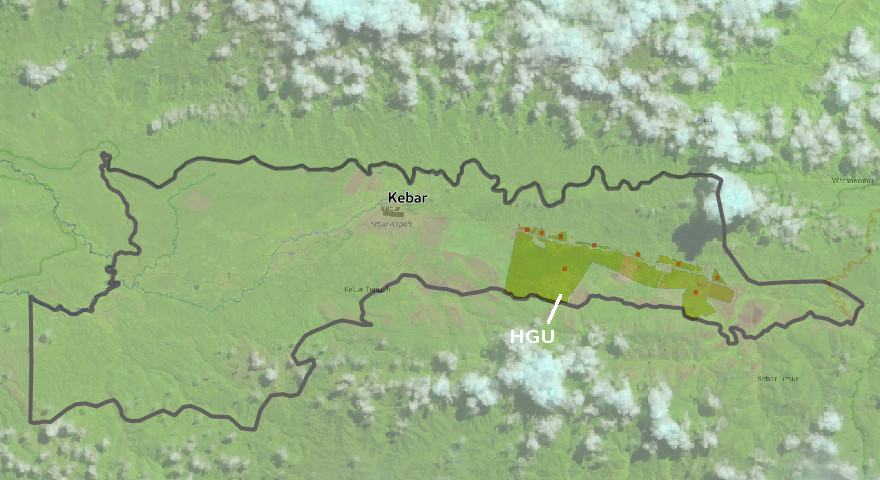

It also appears that the company has used this flawed business licence and the permission to use indigenous land which it obtained through deception to successfully apply for cultivation rights (Hak Guna Usaha), a 35-year lease, on a portion of the land.

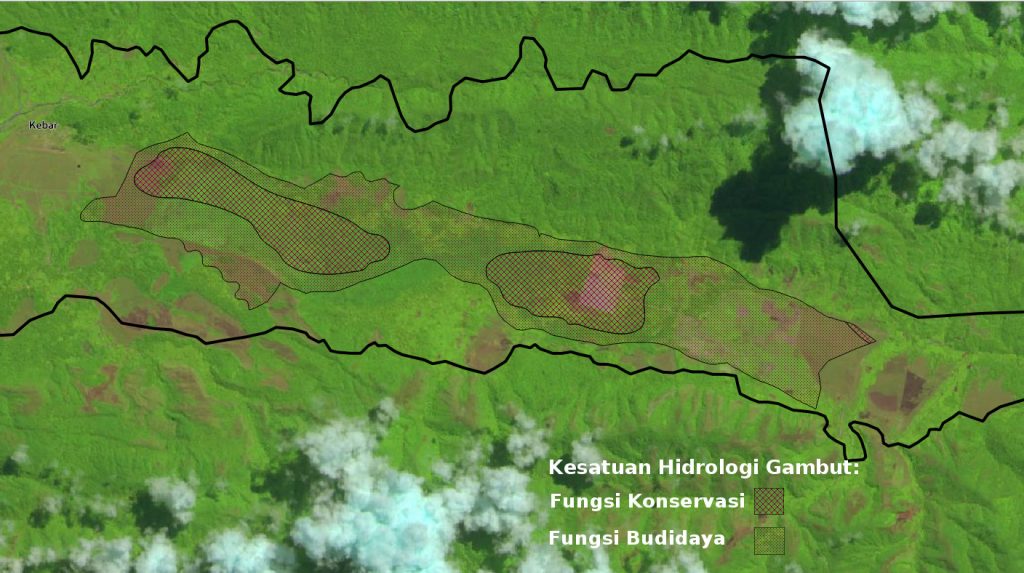

The company is also clearing land which has been established as the ecological zone of a Peatland Hydrological Unit, and so is therefore violating government regulation 57/2016 which prohibits the clearance of these zones, even for companies with existing permits.

This swampland is the main habitat for sago palms which are the traditional staple food of Papuans in the Kebar valley. The company has left a few individual sago trees standing as it clears the other forest, and they now stand surrounded by corn plants with no chance of surviving in the long term now the wetlands are drained.

PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa is one of six plantation companies in Papua linked to the Salim Group. Three are actively clearing forest: PT Rimbun Sawit Papua, PT Subur Karunia Raya and PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa, and there is known to be active community opposition in all three Three more are believed to have all the key permits required to operate: PT Menara Wasior, PT Tunas Agung Sejahtera and PT Permata Nusa Mandiri.

None of these companies are directly owned by Antoni Salim himself, but there is ample evidence that they are controlled by the group, possibly through nominee agreements which allow a beneficial owner to stay off the share register. The Salim Group has never publicly denied its links to these plantation companies, which are currently operated as the Indogunta Group.

As one of Indonesia’s largest processed foods producers, the Salim Group is a major consumer of corn. Much of this is used by its snack food business, which it’s Indofood business operates in a joint venture with Pepsico. This company, Indofood Fritolay Makmur has the franchise for Pepsico products in Indonesia, including corn snacks Cheetos and Doritos. Acting on a specific complaint about workers’ rights in the Salim Group’s IndoAgri oil palm plantations, and non-specified other complaints about the groups deforestation and social/land conflicts, Pepsico insisted that this joint venture ceased to source palm oil from IndoAgri mills in January 2017. This commitment was for palm oil only, however, it has not made a specific commitment regarding corn.