In May 2016, awasMIFEE published a story titled “The Salim Group’s secret plantations in West Papua”, about four concessions owned by the Salim Group in West Papua. A year and a half later, the Salim Group is still aggressively expanding, and threatening more areas of remote Papuan forest. Evidence connecting these companies to the Salim Group’s established businesses is also becoming clearer.

The Salim Group is a diverse industrial conglomerate that developed rapidly during the Suharto dictatorship as its founder Soedono Salim (Liem Sioe Liong), was the president’s most trusted business partner, and through patronage networks helped his family members and cronies build up their own business empires. When the government and economy collapsed in 1998 Salim was hit harder than most, but his son Anthony has rebuilt the empire. The company’s best known brands are under the Indofood label, including Indomie instant noodles, which are sold around the world.

The Salim Group’s main plantation division is Indofood Agri Resources, which is listed on the Singapore stock exchange. Anthony Salim is the President Director of Indofood (the parent company of Indofood Agri Resources) and holds a significant stake (although not a majority). However, there is another oil palm grouping, which has not been widely publicised as being as part of the Salim Group. It was previously referred to in job adverts etc. as the Gunta Samba group, but now seems to be trading as the Indogunta Group. Known plantation concessions under this group are all located in Kalimantan and Papua. The Indogunta Group’s structure, and the evidence linking it to the Salim Group, will be examined in detail below.

The Indogunta Group in Papua.

In Papua, the Salim Group has two oil palm plantations and one corn plantation which are already clearing land, all of which started planting since 2014. It also holds two other concessions which are believed to hold most of the permits necessary to operate, and potentially several more which still lack important permits. Conflicts between the company and local indigenous people have been reported in some of these concessions, and there is a high risk that they will emerge in others.

PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa

PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa has been the source of conflict in the Kebar Valley, in Tambrauw Regency in Papua Barat province in the second half of 2017, when it significantly expanded the area it was planting with corn.

There is clear local opposition to the plantation: On 17th November 2017, 44 local indigenous landowners signed a statement of opposition organised through the Evangelical Christian Church in Tanah Papua (Gereja Kristen Injili di Tanah Papua).

“Since a corn plantation arrived in the Mpur people’s ancestral land (to be precise, in Wasabiti, Amawi, Wanieri, Arui, Kebar and Ariks in East Kebar sub-district) in August 2015, brought to the area by PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa, many areas of Sago have been cleared, historic sites and objects have been lost, the habitats of animals and other forms of biodiversity have been wiped out, the arrival of the corn plantation brings with it the possibility of social conflict between families and sub-clans, and such conflicts could also occur between sub-ethnic groups in the Kebar area” (( “Sejak kehadiran perkebunan jagung di wilayah adat Suku Mpur tepatnya di Wasabiti, Amawi, Wanimeri, Arui, Kebar, Ariks di Distrik Kebar Tiur pada Agustus 2015, yang dibawa oleh PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa, banyak areal dusun sagu yang tergusur, hilangnya situs-situs dan benda bersejarah, musnahnya habitat hewan dan keanekaragaman hayati lainnya, kehadiran kebun jagung memberi peluang terjadinya konflik sosial di antara keluarga dan sub-sub marga dan bisa terjadi antara sub-sub- suku di tanah Kebar.” ))

A statement by the Kebar Valley Defenders Front (Front Pembela Lembah Kebar), issued on 28th November, claims that the indigenous landowners were never involved in and meetings or negotiations with the company or the government. (( “Masyarakat Pemilik Hak Ulayat TIDAK PERNA TERLIBAT DAN/ATAU DILIBATKAN dalam sebuah pertemuan atau NEGOSIASI yang dilakukan oleh Pemerintah dan Pihak Perusahaan” )) Students from Kebar have also launched an online petition which had attracted over 6700 supporters at the time of writing.

The full story of how the Salim Group came to be planting corn in the Kebar Valley is still not properly understood by its opponents. The concession was originally awarded to the company when the area was still part of Manokwari Regency, and an in-principle permit to release land from the forest estate for an oil palm plantation was issued in 2009, the same year as the new Regency of Tambrauw was created. The company was effectively dormant for years, but then in July 2014 was bought by the Salim Group. It is unclear whether it even still held a valid location permit for an oil palm plantation at that stage.

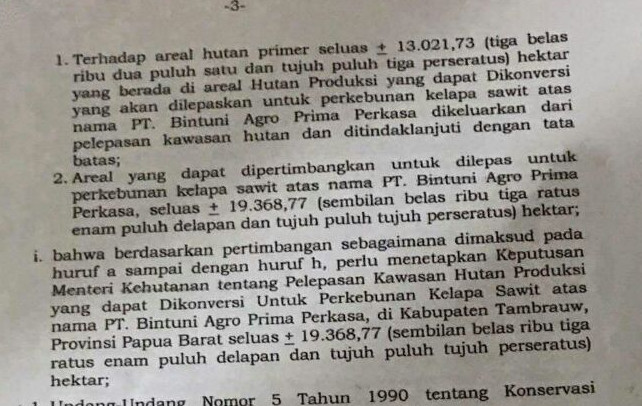

The land was eventually released from the forest estate on 29 September 2014, one of a last minute rush of permits issued by the former forestry minister Zulkifli Hasan on his last day on the job. In common with many other permits issued at this time, Hasan violated his own ministry’s regulations by releasing forest land to a company which did not have an environmental impact assessment approved. However in the case of PT BAPP he made another careless mistake by inadvertently releasing a larger area than intended. In the decree (Surat Keputusan) describing the land to be released it states that 19,368 hectares was to be released, less than the area applied for because 13,021 hectares of primary forest would not be released. However, the maps which accompanied that decision are for an area of over 32,000 hectare, with all the primary forest included.

The forest release decree explicitly states it was for an oil palm plantation, and it is still not clear how or why the company would later use this permit to plant corn. The Bupati of Tambrauw issued a letter 551/296/2015 in September 2015 which is thought to be a new location permit. A request by local activists to get a copy of this document was denied (even though it should be public information). The Bupati has reportedly suggested the permission was for a two year trial period and will not be renewed due to opposition, but has produced no written evidence to confirm this. A hearing for an Environmental Impact Assessment was held in Sorong on 29th September 2016, but once again, when local activists asked to see a copy of this document they were refused.

The Kebar valley, a wide valley around 600 metres high and surrounded by the Tambrauw mountains, is an area of ecological and cultural importance. The valley bottom is a mixture of savannah and woodland, unique in Papua Barat province, and a celebrated local species is the medicinal plant Biophytum Petersianum (known locally as rumput Kebar), which grows nowhere else in Papua, but is found in other continents. In the primary forest in the west of the concession, local people have reported that tree kangaroos are still present, and the mountain slopes provide habitat for the Vogelkop bowerbird, known for its unique and individual artistry in the arenas the male constructs to attract a mate.

PT Rimbun Sawit Papua.

PT Rimbun Sawit Papua is has been operating since around 2015, clearing part of the Bomberay plain in Fakfak regency, which is also characterised by mixed savannah and forest.

In 2017 a potentially serious conflict emerged between two different ethnic groups, both of which claim to be the customary land owners of part of the plantation concession. The company paid compensation to the Mor people from Mitimbir village, a sub-ethnic group of the Mbaham. However, the Irarutu people from Aroba sub-district in Bintuni Bay regency also claim the same land.

According to the Irurutu group, they had stated their claim to the company in writing, and had then taken action on the ground several times throughout March 2017, trying to put in place a customary prohibition on land clearing until the dispute was resolved. However, the company continued working, a matter which representatives of the Irarutu people claim have caused increasing anger. According to the Irarutu, state security forces have also intimidated people from their group. Tensions are not only directed at the company – several community representatives have said they were ready to start a tribal war over this issue. (( Statements of members of a delegation of Irarutu people who travelled to Bintuni on 3rd April 2017, to ask the Bupati of Bintuni to intervene in the case, as recorded by a journalist for Metro TV. ))

A member of the Dewan Adat Mbaham-Matta, who was involved in trying to facilitate a resolution, said that the conflict was still ongoing when asked in September 2017.

PT Subur Karunia Raya

PT Subur Karunia Raya was bought by the Salim Group in 2010, and it started to establish a nursery in 2015 after getting the necessary permits. The plantation is located in Meyado sub-district, to the north of Bintuni town in Papua Barat province. It was almost entirely forested before land clearance began, with the forest classified as secondary forest.

While local indigenous organisations and NGOs say they are not aware of any major land conflicts in the concession, there have also been no detailed investigations to ascertain how the land was obtained from its indigenous owners, or whether or not the community consented to the plantation.

(photo posted on 02/02/2017 by Instagram user bondet_phe and tagged #indoguntagroup (don’t translate)

PT Menara Wasior

PT Menara Wasior’s concession is an area of mixed primary and secondary forest to the south and west of Wondama Bay in Papua Barat province. It was acquired by the Indogunta Group in December 2014 from Jef Setiawan Winata, the businessman who also sold PT Rimbun Sawit Papua. The concession is not yet operational, but it moved one step closer on 20th September 2017, when the forestry minister Siti Nurbaya signed decree 16/1/PKH/PMDN/2017 releasing over 28,000 hectares of forest for the company’s oil palm plantation.

There is significant opposition to the company from residents of Naikere, Kuriwamesa and Rasiei sub-districts, who also hold customary land rights over the concession. This was clearly expressed in April 2015 when the company carried out a public consultation for its environmental impact assessment.

It is therefore highly likely that if the company should claim to have obtained consent of indigenous landowners, this will not represent the wishes of the whole community. Moreover aggressive expansion by resource exploitation industries is an especially sensitive issue in the Wondama Bay area. In the year 2000, an incident at a nearby logging concession triggered a wave of repression by the military against indigenous Papuans which has left many people traumatised to this day. Despite the National Human Rights Commission designating the incident a gross human rights violation, there has been no adequate process to address what happened and find a resolution acceptable to the victims. Under such circumstances, to allow new companies to operate in the area when full consent has not been explicitly proven is both irresponsible and cruel.

PT Tunas Agung Sejahtera

PT Tunas Agung Sejahtera was bought by the Indogunta Group in January 2017, the latest addition to its land bank. It owns a 40,000 hectare plantation in a remote part of the southern coast of Papua, in Mimika regency but around 180 km from Timika city, the nearest important town.

Prior to the purchase it was owned by PT Pusaka Agro Sejahtera, a company controlled by the Yasa family, which have specialised in obtaining permits for plantations all over Papua, but then selling them on to new owners which will eventually operate the plantation. Company records indicate that a previous attempt to sell the concession to a different buyer may have fallen through – shares were transferred to an offshore company in August 2013 but reverted to PT Pusaka Agro Sejahtera in June 2016. The company was eventually sold to the Indogunta Group in January 2017.

This pattern of buying concessions from shady middlemen once they have already acquired some or all of the permits they need is a common practice in Papua, but does nothing to inspire confidence that the permits were obtained honestly. Although no indications of irregularities have been obtained concerning permits issued at the local or provincial level, the forest release permit from the ministry is seen as problematic. As with PT Bintuni Agro Prima Perkasa above, it was issued on the last week of Zulkifli Hasan’s tenure as Forestry Ministry, before an environmental impact assessment had been approved, which contravenes ministry regulations. Several months before, the concession area was removed from the map of areas covered by Indonesia’s moratorium on new permits in primary forest, after the company wrote to the ministry claiming the forest was secondary.

No information is available on how the company is approaching indigenous people in the area to negotiate access to the land. However in such a remote area, there is a high risk that the effects of plantation development will be especially severe for the Kamoro people who live in the area and are highly dependent on the forests and rivers there.

Concessions in Mappi Regency.

In 2013, four Indogunta Group companies were awarded location permits for plantations in Assue sub-district, a remote area in the north of Mappi Regency in the south-east of Papua Province. The companies were PT Putra Palma Cemerlang, PT Remboken Sawit, PT Ekolindo Palm Nusantara and PT Ekolindo Palm Lestari.

There has been no news of any further permits issued to these companies, and so it remains unclear whether they are continuing with investment plans or not. In June 2015, the ownership of all four concessions was reorganised. After this time, only PT Ekolindo Palm Lestari can be confirmed as still having strong links to the Salim Group. (( It is owned by PT Purwa Wana Lestari, which is in turn owned by Soenardi Winanto, a key individual in many Salim Group companies. PT Purwa Wana Lestari also holds a minority stake in two concessions majority-owned by IndoAgri – PT Gunta Samba and PT Multi Pacific International. ))

An overview of the Indogunta Group.

The Indogunta Group is not a traditional corporate group in the sense of a parent company owning different subsidiaries. However, a set of concessions in Kalimantan and Papua appear to share a common management, and this grouping sometimes brands itself as the Indogunta Group. The Papuan concessions are described above. Kalimantan consessions believed to be a part of this group include PT Duta Rendra Mulia and PT Sawit Khatulistiwa Lestari in West Kalimantan, PT Sawit Berkat Sejahtera in North Kalimantan and PT Gunta Samba Jaya, PT Berau Sawit Sejahtera, PT Wira Inova Nusantara, PT Duta Sejahtera Utama, PT Cipta Palma Sejati, PT Wahana Tritunggal Cemerlang, PT Perdana Sawit Plantation, PT Sawit Golden Prima, PT Wahana Murni Plantation PT Sawitindo Plantation and PT Anekareksa International in East Kalimantan.

The direct owners of all these plantation companies are one or more of the following companies: PT Andhika Wahana Putra, PT Mulia Abadi Lestari, PT Cahaya Agro Pratama, PT Bumi Surya Kencana or PT Citra Kencana Kasita. ((The only exception is PT Sawitindo Plantation, which is owned by two individuals.)) These are all holding companies, with no other known assets than the plantation companies. In some cases there are several more levels of holding companies before the ultimate owners are revealed. However, these owners have been traced and they are all individuals.

Anthony Salim is the official owner of PT Citra Kencana Kasita, which owns a majority share of PT Duta Rendra Mulya. However, his name does not appear on the share register of any other company, nor does that any known family members. The assertion that these are Salim Group companies therefore needs to be defended.

How can we be sure this is the Salim Group? Legal vs. Beneficial Ownership.

The fact that the shares in most of these plantation companies are owned by individuals other than Anthony Salim or his family should not be read as proof that the companies are not part of the Salim Group. It is very common in Indonesia for companies to conceal their beneficial owners behind a legal owner who has agreed to use their name on the share register. The beneficial owner would control the company through a series of notarised contracts.

A similar case was highlighted in December 2017 by an Associated Press investigation which found that many companies supplying timber to Sinar Mas’s pulp plants, which Sinar Mas claims are independent, are actually registered in the names of individuals working for Sinar Mas’s finance department. This suggests that the companies may be merely held in their name, while other unknown individuals receive the benefit from their business.

Another clear example of concealed beneficial owners was the Menara Group, which between 2007 and 2013 targetted regencies known to be corrupt in Papua and Maluku to get vast areas of concessions in the names of multiple holding companies: seven in Boven Digoel Regency and 28 in the Aru Islands. Each of these companies had two individuals as shareholders, different people for each of the other companies, yet the companies referred to themselves as ‘Menara Group’ and applied for permits at the same time. Clearly there is no way that most of these shareholders were anything other than proxies for the people who were really in control – known to include politicians and a former national police chief and ambassador.

The relationship by which a legal owner (ie official shareholder) surrenders control to a beneficial owner is known as a nominee agreement. This is technically illegal in Indonesia under article 33 of the 2007 law on capital investment (UU 25/2007) which bans investors from making an agreement whereby shares in a limited company are owned in the name of someone else. (( Pasal 33 ayat 1: “Penanam modal dalam negeri dan penanam modal asing yang melakukan penanaman modal dalam bentuk perseoran terbatas dilarang membuat perjanjian dan/atau pernyataan yang menegaskan bahwa kepemilikan saham dalam perseroan terbatas untuk dan atas nama orang lain.” )) However, many companies have been getting around this law by using a technique known as an indirect nominee agreement in which they create a set of agreements, each dealing with a different aspect of a shareholders rights, which when taken together form the effective equivalent of a direct nominee agreement. This strategy falls into a legal grey area, where it would be difficult for a judge to prove that the law had been broken.

Both Transparency International and the Corruption Eradication Commission have called for more transparency on beneficial ownership of limited companies in Indonesia.

The Salim Group could be expected to have more experience than most companies in finding ways to conceal the true beneficiaries of its business ventures. In the 1950s, as Liem Sioe Liong was getting started in business, the government placed major restrictions on the rights of non-citizens to own businesses, which affected many Chinese-born entrepreneurs. Consequently he was forced to use the name of an Indonesian citizen to register his businesses at the time. (( Liem Sioe Liong’s Salim Group, Richard Borsuk and Nancy Chng, ISEAS Publishing, 2014, p51 )) Later, as Suharto’s preferred business partner, he was expected to raise finance from the business community to support Suharto’s plans and ensure his preferred party won elections, and then helped to ensure the fortunes of Suharto’s children. A lack of transparency over share ownership would have made it much easier to establish these patronage networks.

After the 1998 collapse, many Salim assets were transferred to a company called Holdiko Perkasa to pay the group’s debts. Anthony Salim is believed to have tried to buy back some of these assets, using proxies, which was not illegal until interior minister Rizli Ramli banned former conglomerates from recuperating seized assets in 2000. There is unproven speculation that Salim continued to use proxies after this, including media tycoon Hary Tanoesoedibjo. (( Liem Sioe Liong’s Salim Group, Richard Borsuk and Nancy Chng, ISEAS Publishing, 2014, pp 432-443 )) Whether he did or not, he was surely aware of the legalities of the various techniques for doing so.

While the existence of nominee agreements cannot be conclusively proved in this case, there is more than enough evidence to link the Indogunta companies to the Salim Group. Indeed, the groups do not go to any great length to conceal the link: the typeface and graphics used on the Indogunta and IndoAgri logos are identical.

Here are six more key links between the Indogunta Group and the wider Salim Group:

-

Company representatives have said it is the Salim Group: In 2015, Cornelis Luther was presenting PT Menara Wasior’s plans to local people at a public meeting in the area, and said “PT Menara Wasior is one of… maybe hundreds of subsidiaries of the Salim Group.” (( “PT Menara Wasior adalah satu dari… sekian ratus anak perusahaan Salim Group” )) Cornelis Luther is assistant head of PT Duta Rendra Mulya, one of the companies where Anthoni Salim is the legal owner.

-

IndoAgri Group companies and Indogunta Group companies share offices. Many Indogunta Group companies are registered to addresses in the Duta Merlin Office Complex in Central Jakarta, including Blok B.22-23 which is also the office of IndoAgri subsidiaries PT Gunta Samba and PT Multi Pacific International.

-

Indogunta Group plantations have been financed by other Salim Group companies. In 2009 and 2010 Indomarco Prismatama, owner of the Salim Group supermarket chain Indomaret, purchased interest-free bonds worth 428 billion Rupiah in one of the Indogunta Group holding companies, PT Andhika Wahana Putra, which were convertible to a 50% stake in the company.

-

Some staff members associate the IndoGunta and IndoAgri groups on their linkedin accounts. https://id.linkedin.com/in/finan-amanda-s-e-54067710a https://id.linkedin.com/in/sucipto-cipto-3823a919

-

Ownership of concessions has moved between the group. In 2007, one of the Indogunta Group holding companies, PT Mulia Abadi Lestari sold 70% stake in a concession, PT Mitra Inti Sejati, to Indo Agri, and the remaining 30% in 2008. In 2006, PT Gunta Samba was incorporated into IndoAgri while PT Gunta Samba Jaya became part of PT Andhika Wahana Putra (Indogunta Group). Prior to this, shares in both companies were owned by key executives in the Salim Group, Sinarman Jonatan and Soenardi Winanto.

-

Anthoni Salim is a former general director of PT Unitama Adiusaha Shipping, which owns 50% of PT Andhika Wahana Putra.