There is currently some momentum for change in the palm oil industry, aiming to reduce its disastrous environmental and social impact. In Papua, some of the biggest companies, such as Sinar Mas, Musim Mas and Wilmar, have all abandoned plantation plans after signing up to ‘no deforestation’ policies. ((in the case of Wilmar, the abandoned plantations would have planted sugar-cane.)) The Indonesian Government may also finally take some action to bring the industry under control. A new moratorium on palm oil permits is reportedly being prepared and the Forestry and Environment Minister Siti Nurbaya has made clear that one of the moratorium’s main objectives is to save Papua’s forest.

However, many companies with ambitions to vastly increase their plantation area are still looking to Papua as one of the few areas where large amounts of land are still potentially available. Plantations on this new frontier are often much larger than elsewhere in Indonesia, meaning huge environmental destruction and drastic changes which have a devastating effect on local indigenous populations.

Accurate information on how the oil palm industry is developing in Papua is crucial to be able to assess whether the changes in the industry will actually protect the forest and make a positive difference to the lives of indigenous Papuans, or if it will just give a better image masking the same old problems. Nevertheless, obtaining full data is still a major challenge. This series of articles aims to give it a shot, profiling a few of the newest companies to start operations in Papua, especially companies which have recently started cutting the forest, or appear to be preparing to start work. The first is a particularly worrying case, where forest clearance started last year: Pacific Inter-link.

…

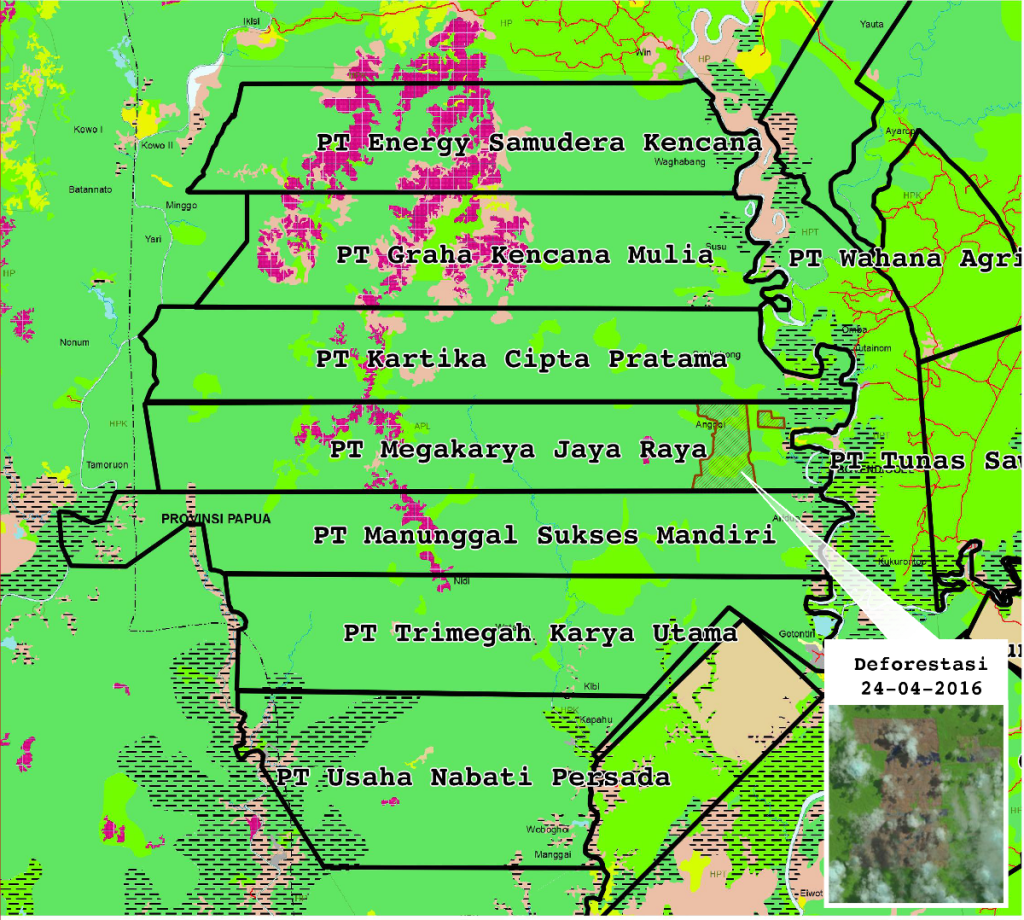

In a remote area of Southern Papua an immense block of 2,800 square kilometres (the size of Luxembourg, or three times Singapore) of primary rainforest has been given permits for oil palm, and deforestation has already started. In an incredibly brazen move by local politicians, (later supported by the Forestry Ministry), this whole area was given away to just one company, the Menara Group, divided into seven contiguous concessions.

The Menara Group has since sold most of the concessions to two Malaysian-based companies: Pacific Inter-link took four of the concessions (PT Megakarya Jaya Raya, PT Kartika Cipta Pratama, PT Graha Kencana Mulia and PT Energi Samudera Kencana) and Tadmax Sdn Bhd took two (PT Trimegah Karya Utama and PT Manunggal Sukses Mandiri). The remaining concession, PT Usaha Nabati Terpadu, either still belongs to the Menara Group or has been sold to an unknown buyer.

Pacific Inter-link started work on one of the concessions, PT Megakarya Jaya Raya in mid 2015. Satellite images show that by April 2016, 2,840 hectares of forest had been cleared. About one third of that area was on deep peat, and the area lies within an intact forest landscape. Most of PT Megakarya Jaya Raya’s concession is classified on Indonesian government maps as primary forest, as are the other three concessions.

It isn’t easy to greenwash the conversion of 160,000 hectares of primary rainforest to palm oil plantation. Nevertheless, Pacific Inter-link makes a lame attempt to do just that on its website, stating that “Lots of careful measures are taken to ensure no ecological damage takes place due to this project.” The company did not respond to a request to view high conservation value assessments or social and environmental impact assessment.

How did one company manage to get its hands on so much land? There are no local groups in this remote area which have been able to undertake a full investigation. However, corruption must be suspected. The Boven Digoel Regency Head, Yusak Yaluwo, issued the initial location permits in July 2010, three months after being arrested on unrelated corruption charges. He was found guilty in November that year, and declared non-active by the interior minister. Nevertheless, despite being imprisoned in Sukamiskin Prison, Bandung, there were frequent allegations that Yusak Yaluwo was continuing to run the Boven Digoel government from his prison cell by mobile phone. He was officially removed from his post in May 2013, but wasn’t formally replaced by his deputy until June 2014. The upshot of this bizarre story is that there was no effective local government in Boven Digoel for three and a half years, the time which the Menara Group was engaged in the permit process for the plantations which would later be sold to Pacific Inter-link.

At the same time in the Aru Islands in Maluku, the Menara Group had tried to claim an even larger area for a sugar-cane plantation. However, as a strong local campaign was unearthing irregularities at every level, the Forestry Minister eventually declared that the plantation would not go ahead, giving the reason that the land was not suitable for sugar cane after all.

The land which is being cleared is near an indigenous village, Kampung Anggai, but there have been no reports of how the local people view the company, nor what methods the company used to persuade people to allow it to use their land.

Tadmax, the other company involved, has so far not developed its concessions, claiming to be looking for a partner, or to sell the land. Its 2015 Annual report states that “the Group is in the process of identifying parties to undertake a plantation development (both on its own or through joint ventures) and/or outright disposal of all or part of the land or a combination of the above. “

Previously both Pacific Inter-link and Tadmax had signed up to a joint venture in 2012 for an integrated timber complex which would use the wood from their concessions, but there is no recent news that might indicate the plan is still going ahead.

—

Pacific Inter-link is based in Malaysia, but is part of the privately-owned Yemeni conglomerate, the Hayel Sayed Anam Group. Its plantation in Boven Digoel is the company’s first, but palm oil has long been part of its core business and the company has a presence at almost all levels of the industry. It operates refineries on Sumatra, is a trader of crude palm oil which it buys from other plantation companies, and markets consumer goods produced from palm oil under a number of brand names: Avena, Madina, Pamin and Sheeba cooking oils, Saba Juliet and Meditwist Soap and Milgro milk products. As well as South East Asia, Pacific Inter-links products are marketed in the Middle East and Africa, where its brands have a dominant market position.

This high degree of vertical integration in its supply chain insulates Pacific Inter-link from the pressures on other palm oil producers, which have to contend with the possibility that if they continue to deforest, their product may be boycotted by several of the largest palm oil traders.

However, the concessions have caught the eye of Forestry and Environment Minister Siti Nurbaya. In an interview with foresthints.news she described how existing palm oil permits will be reviewed in preparation for a moratorium, “Several of our findings indicate that in areas where forest release permits have been granted since 2011 in Papua, nothing has been done there and they are simply landbanks. We even found that some of these permits have been traded. For example, seven forest release permits for palm oil development in that province [Papua], amounting to almost 300 thousand hectares, were sold to a number of business groups in Malaysia. This practice of trading involves 20 percent of the areas that should be given to communities.”

Pacific Inter-link is an RSPO member as a trading and processing company, but has not mentioned the existence of its plantations in any submissions to the RSPO. Neither has the company responded to requests for information from awasMIFEE.

The situation is extremely alarming: what is likely to be the largest single palm oil plantation development project ever to take place in Indonesia is happening in an area of primary rainforest, containing peat swamps, and with no information whatsoever on how the plantation is affecting the tribes living in one of the remotest areas of Papua. A large area has been cleared already, but this is still only so far only 1% of the total areas under permit. Serious and immediate attention is needed on how the Menara Group, and subsequently Pacific Inter-link managed to get control of such a large area, and it needs to be held to account on its potentially devastating social and environmental impact.